NADI, FIJI – In conversations about climate change, gender is not always considered.

In February 2018, the Government of the Republic of Fiji and the National Adaptation Plan (NAP) Global Network co-hosted workshops to emphasize why gender needs to be integrated into climate change planning and action.

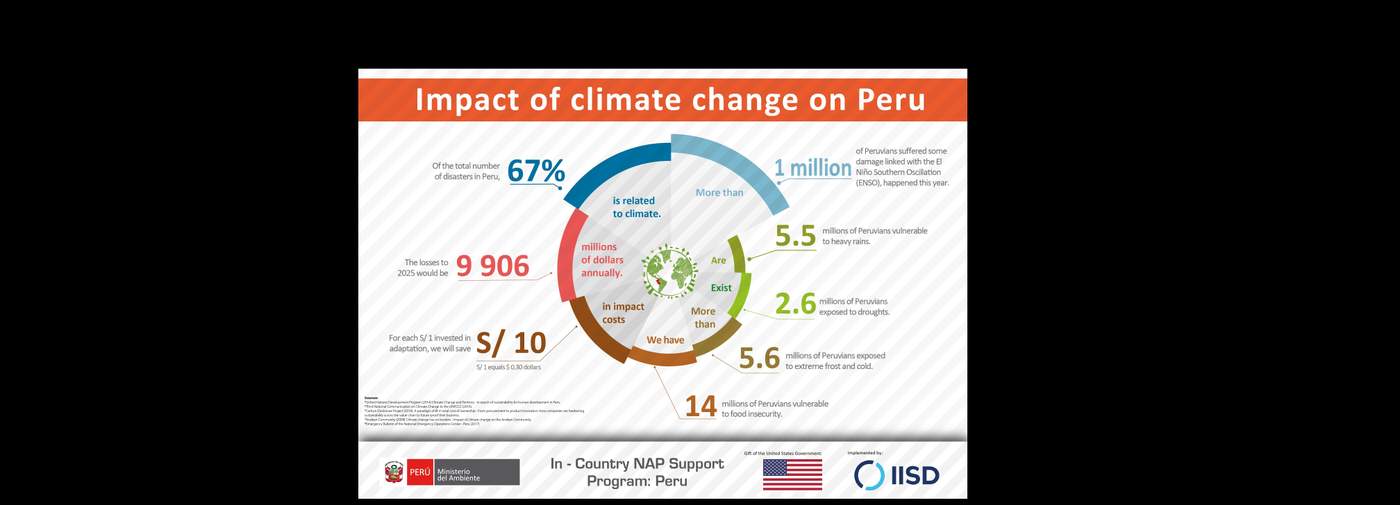

Angie Dazé from the International Institute for Sustainable Development and Maritza Ivonne Yupanqui Valderrama—Director General of Peru’s Department of Gender Mainstreaming from the Ministry of Women and Vulnerable Population—sat down to talk about integrating gender into NAP processes.

AD: It's really great to hear very concrete examples based on this overarching plan, but as we know this is a journey, and despite progress, we are also in the middle of the learning process. I was just wondering if you could share a few closing ideas that you'd like the participants to take away, based on your experience so far?

IV: I would like to share some ideas, which many of you may know already, but I would like to emphasize them.

First, that climate change adaptation is an opportunity to close gender gaps.

The second one is that women are agents of change, and we have to hear their voices.

Third, it is useful and important to have an official plan approved at the highest level because it demonstrates commitment to move these issues forward.

And finally, and this is a phrase I like to say always: women are half of the population, so women should share half of the power.