NAP Process: Guidance on NAPs

-

Are there guidelines for the NAP process?

Yes. In 2012, the Least Developed Country (LDC) Expert Group (LEG), the UNFCCC body tasked with providing support to LDCs in the NAP process, developed technical guidelines that outline the key steps involved in the process. While recognizing that the NAP process must be country-driven and context-specific, these guidelines provide a roadmap for countries in advancing their NAP processes (UNFCCC, 2012). A range of supplementary materials, which offer more focused or in-depth guidance on different aspects of the LEG Technical Guidelines, is also available.

-

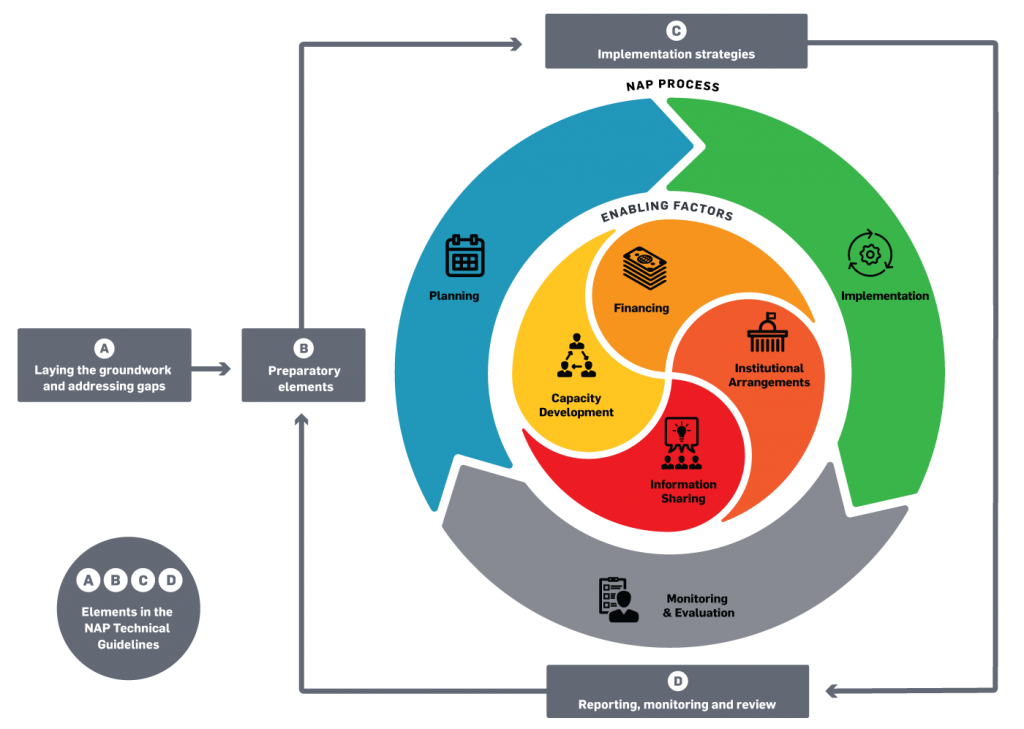

Do these LEG Technical Guidelines correspond to the NAP process diagram presented above?

Yes. Both the LEG Technical Guidelines and the NAP process diagram convey the same process—in fact, you can easily map them against each other. The Technical Guidelines note four elements: A. Lay the Groundwork and Address Gaps; B. Preparatory Elements; C. Implementation Strategies; D. Reporting, Monitoring, and Review. Under each element are a series of 4-5 steps. Broadly speaking, phases A and B can fall under “planning,” phase C under both “planning” and “implementation” and phase D under “M&E” of the NAP process cycle.

-

What is an effective NAP process?

Building on what has been decided through the UNFCCC decisions around enhanced action on adaptation, the NAP process should be:

- Country-driven: Where countries decide what approach, process and deliverables are best suited to identifying and addressing their adaptation priorities.

- Gender-responsive: Where gender differences in adaptation needs and capacities are recognized, participation and influence in decisions equitable, and benefits resulting from investments in adaptation equitably accessible.

- Participatory and fully transparent: Where a wide range of stakeholders both within and outside of government—i.e., sub-national authorities, academia, civil society, the private sector—can take part in the NAP process, and the process itself is open, communicative and accountable.

- Inclusive of vulnerable groups, communities and ecosystems: Ensuring that adaptation investments are targeted where they are needed most, recognizing the acute vulnerability of marginalized groups and communities and the need to protect and build resilience of ecosystems.

- Multi-sectoral, where inputs and commitment from multiple sectors and ministries—not just that of the environment ministry—are secured and sustained. Climate-sensitive sectors (e.g., agriculture, health, water and sanitation, infrastructure), as well as the planning and finance ministries must be at the table.

- Guided by the best available science and, as appropriate, traditional and Indigenous knowledge: Informed by the latest validated data and information on climate risks and vulnerability, recognizing that there will be uncertainties and limitations. This can also include drawing from the knowledge, innovations and practices of Indigenous and local communities.

- Continuous: Established and managed with an expectation that a country’s climate risks and adaptation needs will be assessed on an ongoing basis; it is a sustained process of revisiting priorities and integrating them in decision making.

- Iterative: Related to “continuous,” the process should be adjusted and repeated to consider new data and information, as well as lessons and results from previous phases and rounds so that it improves.

- Coordinated, avoiding duplication so that the different analyses, consultations, and outputs that comprise a NAP process do not repeat what has already been done or is underway through other initiatives; indeed, the aim is to bring different adaptation efforts together so they can build on each other and offer a more consolidated and coherent articulation of a country’s adaptation priorities.

-

What about a NAP document—is there a recommended structure, table of contents or other specific criteria?

There is no one-size-fits-all template for a national adaptation plan document. The most important thing is that countries develop something that is meaningful and useful in their respective contexts.

In terms of structure, some countries may opt for one single overarching National Adaptation Plan; others may decide that separate sectoral adaptation plans/strategies make more sense. Yet others may do both—i.e., develop an overarching plan supplemented by stand-alone sectoral plans/strategies. Again, there is no single approach—a country’s NAP team needs to assess what works best in their country’s context.

For content, the most important thing is for a country to describe its medium- and long-term adaptation needs and priorities along with strategies for addressing them. This could be accompanied by a country’s longer-term vision for adaptation, as well as the principles, perceived purpose, scope and added value of its NAP process. Some institutional context might also be provided, where relationships between the NAP process and other relevant policies and plans are described.

The extent to which countries dedicate sections of their NAP document(s) to summarizing the risk and vulnerability context, adaptation efforts to date, the governance structures behind adaptation decision making, or the process underpinning the development of the NAP document itself—this is at each country’s discretion.

Whatever the structure and range of content, NAP documents should be strategic. They should not only clearly articulate a country’s adaptation priorities, but also define how they will be achieved, by whom, and over what time frame. Both in-country stakeholders and external actors—such as development partners and private sector investors—should see it as a guide for where adaptation investments are needed. Ideally, the document should also describe what the next steps in the NAP process will involve.

Whatever approach is taken, countries should remember that the process behind the development of a NAP document is just as important—if not more—than what gets published. A document is not the end goal of a NAP process.

-

Speaking of NAP documents—what is the difference between a NAP roadmap, NAP framework and NAP document?

The NAP process often involves the development of several documents—not just a final adaptation plan or set of adaptation plans. The most common amongst these are:

- NAP roadmap, which provides an overview of what needs to be done for the NAP process; it spells out the key steps, activities, roles and responsibilities, necessary resources, and timeframe for the NAP process.

- NAP framework, which provides an overarching vision and structure for the NAP process, including an articulation of its added value. It describes the mandate, objectives, principles and overall approach of the NAP process, and aligns it with the broader policy landscape. It may also go as far as identifying specific sectors and themes that are especially relevant to the country’s context.

- NAP document(s), which is a strategic document (or set of documents) that identify a country’s medium- and long-term adaptation priorities, and the strategies for addressing and tracking them. It can also describe how a country will go about embedding adaptation into its development planning, decision-making and budgeting processes.

Once a final NAP document is produced, other documents may be developed to push the plan towards implementation. These may include implementation plans, resource mobilization strategies, financing strategies, concept notes and funding proposals.