Scaling up Climate Resilience in Benin: The launch of the country's first National Adaptation Plan

Thomas KPONOU, a teacher from the Aguégués lakeside community (located between Porto-Novo and Cotonou, Benin’s two largest cities) remembers the historic flood of 2010 vividly. Over 680,000 people were directly affected across the country. Houses and schools were invaded by the water, and many were caught surprised, leading to 56 deaths.

Over the past 40 years, Benin has experienced several extreme meteorological and climatic events that have led to lost lives, livelihoods, and homes. And the economic losses are enormous. When Benin was again struck by devastating floods in 2019, damages were estimated at around CFA 53.3 billion (approximately USD 85 million).

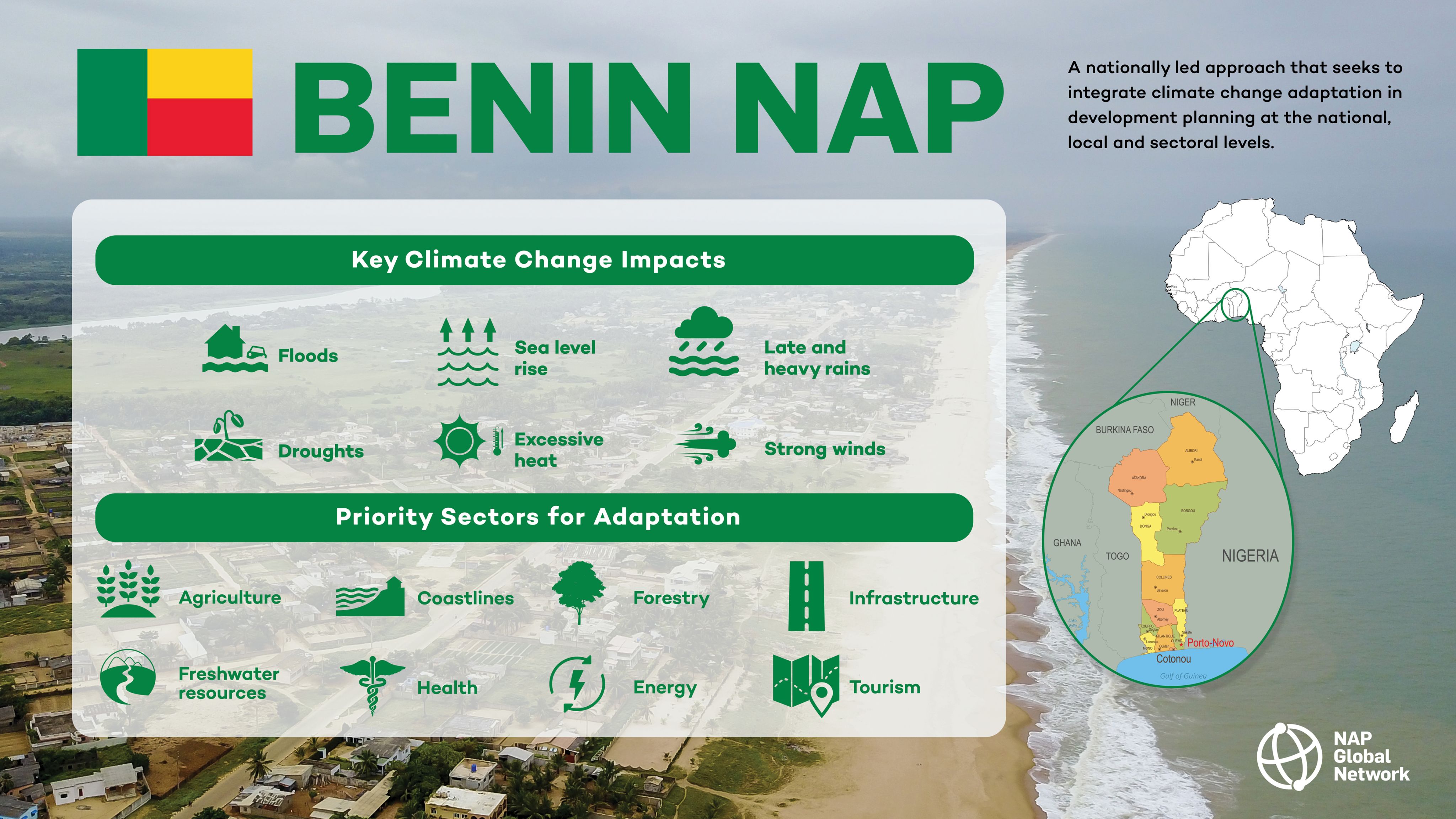

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) issued a clear and renewed warning in its 2022 report on Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: due to human-caused climate change, countries around the world will be more exposed to more frequent and intense climate hazards in years to come, including catastrophic floods, droughts, heat waves, erratic rainfalls, sea level rise, and heavy winds.

The impacts of climate change are already being felt today by the people of Benin, and the projected consequences are concerning. Benin faces current and future threats of deteriorating ecosystems and natural resources, coastal erosion, lost agricultural production, lost livelihoods and income, degradation of infrastructure, weakening of health and socio-economic services, and communities being displaced.

To prepare for these threats, adapting to the climate crisis is imperative for Benin in order to protect its people, nature, and economy—and to secure a prosperous future.

In the village where Thomas lives, all houses are built on stilts. Managing climate risk in this context means—first and foremost—managing the rising water levels. “After the rains of 2010, we had to change things and elevate the height of our constructions.”

While such actions can help in the short term, keeping pace with climate change will require the urgent scaling-up of many similar adaptation actions—a core aim of Benin’s National Adaptation Plan process.

Watch Thomas KPONOU's full interview.

The NAP process, in simple terms, is a “strategic process that enables countries to identify and address their medium- and long-term priorities for adapting to climate change. Led by national governments, the NAP process involves analyzing current and future climate change and assessing vulnerability to its impacts. This provides a basis for identifying and prioritizing adaptation options, implementing these options, and tracking progress and results.” (The official definition, objectives, and guidelines of the NAP process are available via the UNFCCC website).

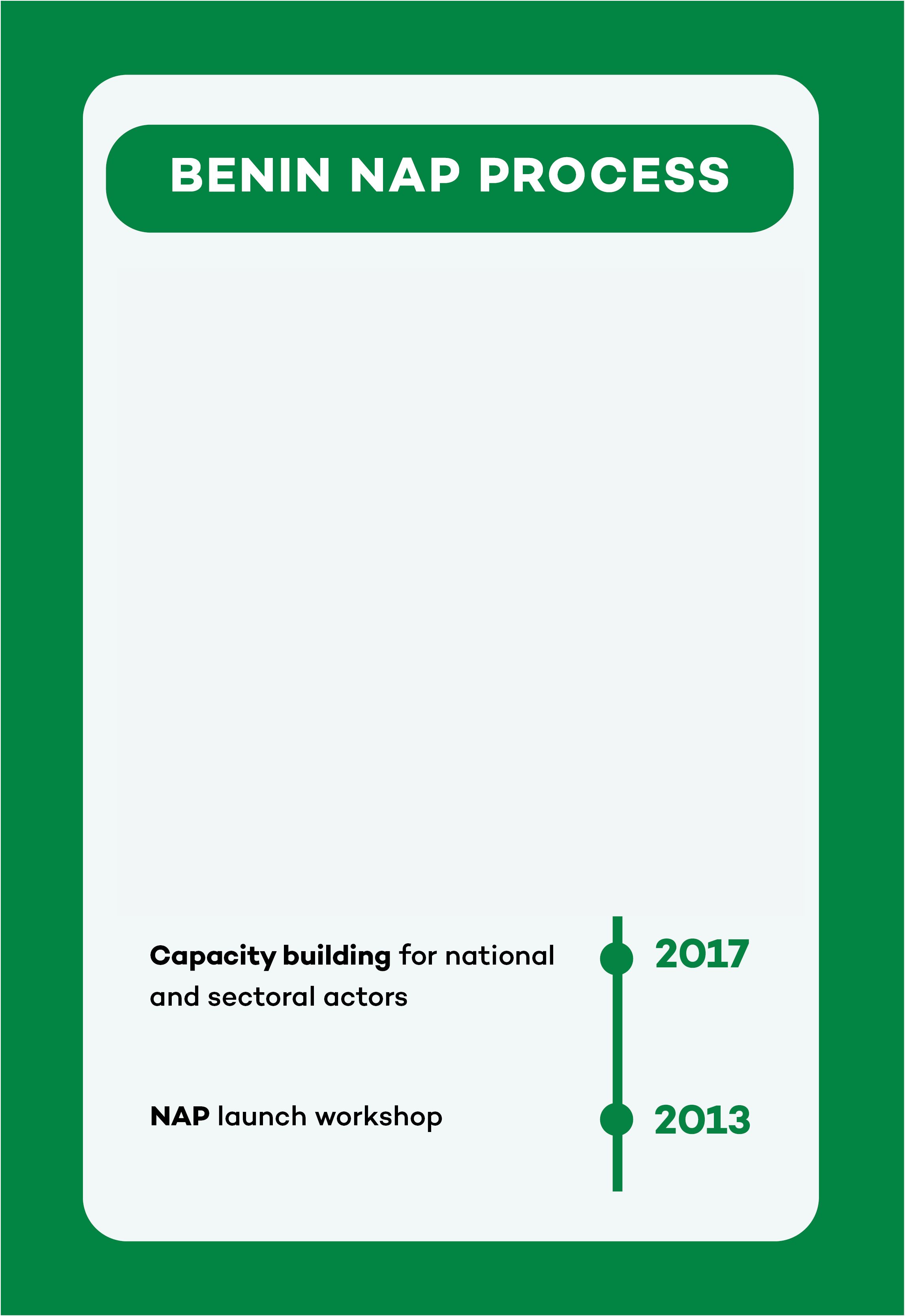

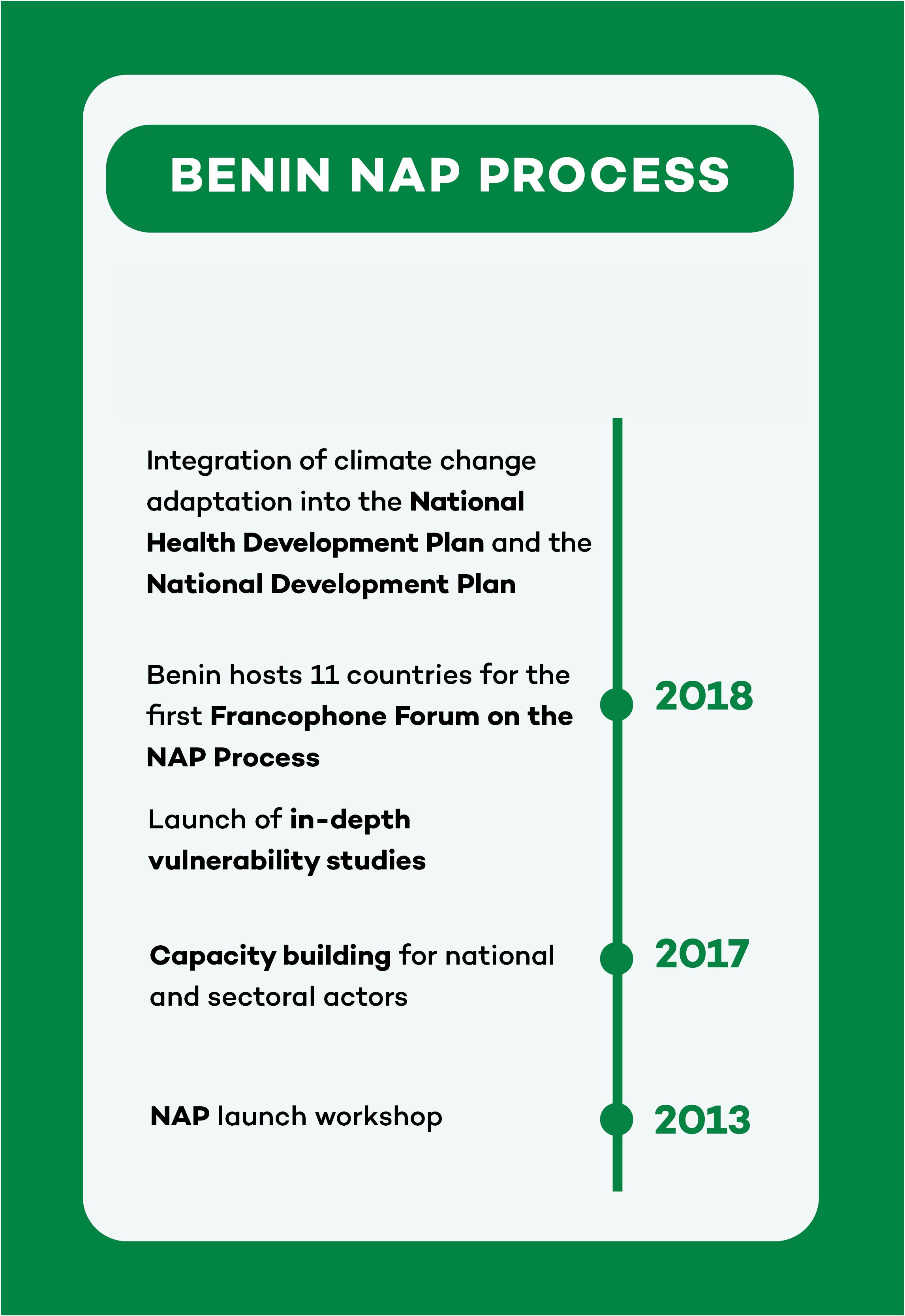

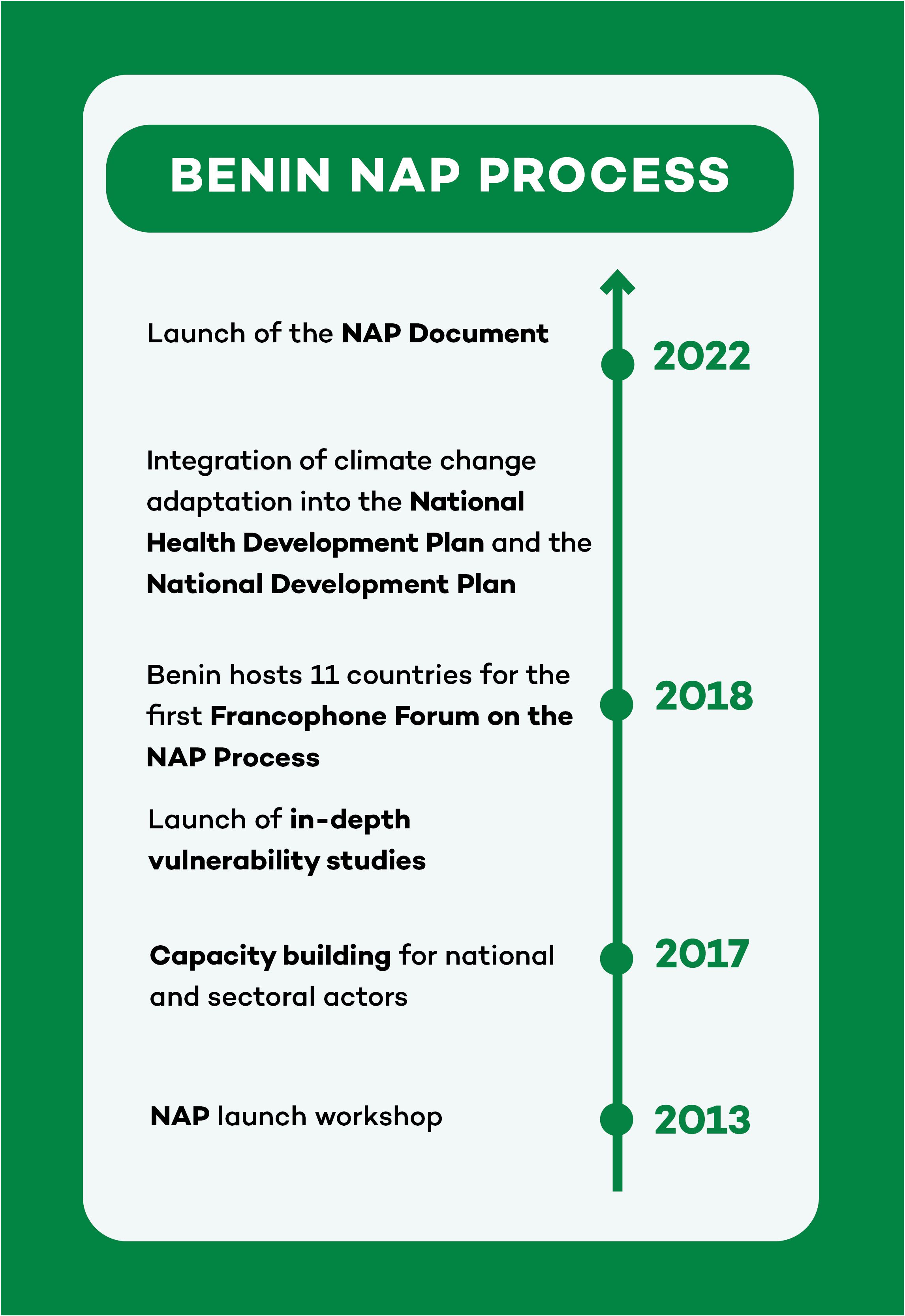

In 2013, the Government of Benin launched the NAP process under the leadership of the Ministry of Living Environment and Sustainable Development (MCVDD) to establish the country’s medium- and long-term adaptation vision and priorities and to ensure that climate adaptation is integrated within all existing and new development policies, strategies, plans and budgets.

Sectoral vulnerability studies were conducted with the support of two partners: the Support Project for Science-based National Adaptation Planning (PAS-PNA)—funded by the International Climate Initiative (IKI) of the German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMU)—and the National Adaptation Plan Project (PPNA) of the United Nations Development Program (UNDP).

Using climate modelling and a participatory bottom-up approach, these studies were essential in supporting decision making and identifying the main climate challenges, adaptation options, and resources needed.

Submitted to UNFCCC on July 08, 2022, Benin's first NAP defines a clear set of adaptation actions to build resilience to climate change in eight key sectors: agriculture, water resources, health, coastal zones, forestry, energy, infrastructures and urban development, and tourism. These are complemented by one cross-cutting theme dealing with gender, vulnerable groups, Indigenous Knowledge, and migration issues.

Accelerating Adaptation Actions in Priority Sectors

To achieve its vision for building nation-wide climate resilience, Benin’s NAP process builds on an established track record of adaptation action.

Adaptation in Agriculture: Drought-resilient farming in the Savalou Hills

Agriculture and food security have been a priority sector for all developing countries that have communicated NAPs to the UNFCCC to date.

Benin’s agricultural sector is especially vulnerable to climate change and a top priority for protecting livelihoods, as it represents 32% of the GDP and 75% of the country’s exports.

For many farmers, applying sustainable agro-ecological and water conservation practices has been key in fighting against droughts.

In Benin’s Savalou Hills, farmer Benoit HODONOU says, “Technicians advised us to plant legumes to retain moisture in the soil. This solution has helped us deal with pockets of drought and reduce losses.”

He praises the Soil protection and rehabilitation to improve food security (Protection et Réhabilitation des sols pour améliorer la sécurité alimentaire – PROSOL) project that provided this technical advice. “PROSOL has come as a relief to us. While other farmers complain about the scarcity of rains, we still benefit from the moisture in our fields. Maize, cassava, and groundnut yields have actually improved.”

Watch Benoit HODONOU's full interview.

Fellow producer Agondo HOUELONON has also seen benefits from planting the moisture-retaining legume mucuna: “We sowed mucuna in my field…then after the first rain there was a pocket of drought that lasted for about a month. My neighbours lost everything, while I still had income.”

Mucuna beans.

Mucuna beans.

Benin’s NAP seeks to accelerate the adoption of such climate-resilient adaptation techniques. It outlines a broad set of goals for the agriculture sector that include increasing investments in capacity building for farmers, research on drought-resistant crops and improved varieties, the dissemination of climate information and innovative agricultural technologies, the promotion of good governance, and the facilitation of women’s access to land, among other planned activities.

Sharing Climate Information with Producers Through Communications Technology

Though French is Benin’s official language, there are 55 languages spoken in the country, and French is the second language for most francophone Beninese. This rich linguistic diversity can pose challenges for sharing relevant information for enhancing local communities’ resilience.

One start-up company, Tic Agro Business Center (TIC-ABC), is using communications technology to overcome this gap. In the region of Toucountouna, in northwestern Benin, TIC-ABC shares messages with farmers in Waama, their local language.

“They receive information related to climate or information on seeds to know how to react to different climate conditions,” explains Donald TCHAOU, director of TIC-ABC.

Watch the interview with the farmer Elie TANTOUKOUTE on how he has benefited from the communication in his own language.

In 2021, over 10,000 Beninese farmers used the tools developed by TIC-ABC, providing them with the critical information they need, such as agro-meteorological data, best period of sowing, availability of agricultural inputs, epidemic alerts, reminders on the dates of phytosanitary treatments, best periods for selling products, and their prices in the market.

The company is now partnering with UNDP and GIZ to deliver agriculture-related info in local languages in more regions of Benin and expanding its efforts.

In addition to reaching farmers through cell phones and smartphones, the company also shares good agricultural practices through a mobile video-projection system. “We gather the producers in a public space, and we show the videos which are generally in their local language followed by an explanation. The next day we hold practice sessions with the producers on the content of the videos,” adds TCHAOU.

The Government of Benin’s National Adaptation Plan recognizes the role private sector actors like TIC-ABC play in scaling up national efforts to adapt to climate change.

Protecting Coastal Zones from Erosion

Like agriculture, Benin’s coastal zones and tourism sectors face serious climate threats and are priority sectors in Benin’s NAP.

Benin’s 125-km coastline along the Gulf of Guinea has been under severe threat because of multiple stressors. The construction of the port of Cotonou in the 1960s—currently the third largest in Western Africa and responsible for generating 60% of Benin’s GDP—changed the natural dynamics of the coast, resulting in the accumulation of sand to the west of the port and erosion to the east.

Massive urbanization, increasing maritime traffic in the Gulf of Guinea, and more frequent intense storms have accelerated the erosion to the fierce pace of 10 m per year, according to Philippe ZOUMENOU, director of Coastal Protection Ecosystem Preservation of Benin’s MCVDD.

Groynes were built on Cotonou's shore to defend the coastline against waves' onslaught. (Photo: Patrick Guerdat)

Groynes were built on Cotonou's shore to defend the coastline against waves' onslaught. (Photo: Patrick Guerdat)

The government began to address the alarming scale of erosion in 2012 by constructing eight groynes—some up to 300 m long and made with 60,000 tonnes of stones—to defend the coastline against waves’ onslaught, slowing down currents and limiting sediment movement.

Following the devastating high tides of 2016, the government intensified its resilience-building efforts by constructing four additional groynes and 600 m of submerged dikes. Nearly 150 ha of beach was replenished with sand, receding the ocean by 150 m on average. Now a long sandy beach stretches for 15 km east of Cotonou. In addition, a reserve of sand has been formed for future projects in the coastal regions of Ouidah and Grand-Popo.

The restored beach and the creation of a 50-ha seawater lake have enabled the development of recreational and tourism infrastructure in Cotonou.

Nearly 150 hectares of beach were replenished with sand, receding the ocean by 150 m on average. (Photo: Patrick Guerdat)

Nearly 150 hectares of beach were replenished with sand, receding the ocean by 150 m on average. (Photo: Patrick Guerdat)

“We did not just backfill the caissons. We created an additional beach to provide the people with the beach that they had lost. What led to this choice of development was our decision to create a seaside resort,” says José TONATO, Benin’s Minister of Environment and Sustainable Development.

In addition to proposing new infrastructure projects, the NAP seeks to protect Benin’s coastal zones and tourism sectors through the development of a coastal surveillance and governance system; the promotion of conservation projects and ecosystem-based adaptation practices, such as the restoration of mangroves; the preparation of relocation strategies for communities at risk; and the incitement of ecotourism initiatives.

Watch the full interview with Philippe ZOUMENOU, director of Coastal Protection Ecosystem Preservation of Benin’s MCVDD.

Scaling Up Effective, Inclusive Adaptation: Next steps for Benin’s NAP

Achieving the vision for climate resilience that Benin’s NAP sets out will require a cross-government, cross-society approach. Scaling up climate resilience will require adaptation financing; adaptation skills and knowledge to be developed; strong, well-governed institutions working together; and effective communications.

Finance

Implementing all the measures identified in Benin's NAP document and across all sectors will require an estimated USD 4.2 billion from multiple sources—public and private, international and domestic.

The National Environment and Climate Change Fund (FNEC) is one key institution created in 2017 with the mission of financing adaptation, conservation, and sustainable development projects in Benin.

The FNEC is working to secure international finance for adaptation and has been designated as the national accredited entity of the Green Climate Fund (GCF) and the Adaptation Fund. This finance would complement domestic finance already being leveraged. FNEC’s director, Appolinaire GNANVI, explains that a number of domestic financing approaches are already in use: “We have ecological taxes, also called ecotaxes, that are levied so the public can contribute to remediating the damage and harm caused to the environment...these taxes are collected according to the polluter-pays principle.”

Benin’s NAP aims to strengthen the FNEC’s mechanisms as one of several priorities for mobilizing resources for the NAP’s implementation.

Gender-Responsive Adaptation

Recognizing that climate change impacts affect women and men differently, the Benin government is seeking to develop a gender-responsive NAP process by including gender as a crosscutting theme.

The government undertook an analysis of gender considerations in its NAP process in 2019, identifying a number of opportunities for addressing inequalities—including low representation in decision making bodies, lower literacy rates, and inequality in land inheritance—and promoting women and girls’ roles as agents of change through adaptation action.

“Women’s livelihoods are affected by climate change,” says Prisca JIMAJA ABLET, gender and climate change focal point at the MCVDD. She says,“You will see that effort has been made to address gender in this National Adaptation Plan. That’s already progress.”

Click on the image to access the full report.

Click on the image to access the full report.

Managing Risks and Vulnerabilities on Benin’s Road to Resilience

Securing financial resources and integrating gender and social inclusion considerations are just two examples of steps needed to work toward effective, inclusive adaptation action. Other vital steps will be raising awareness about the NAP across government and the general public and establishing a monitoring, evaluation, and learning (MEL) system for the NAP to track progress toward the achievement of its goal and document lessons learned

Watch the ODD TV coverage of the raising-awareness workshop (In French).

"Many actions are being carried out now to enable our population to be more resilient, to be able to cope without forgoing economic growth, because the government has integrated climate change into planning and budgeting.”

Watch the documentary On the Road to Resilience in Benin, produced by the journalists William Appolinaire TCHOKI and Fulbert ADJIMEHOSSOU—English captions available.