"Is there a gender issue?"

Lessons from Jamaica’s Workshop on Integrating Gender into the NAP Process

Introduction

“Do we even have a gender issue here?”

Last month, from September 18 to 20, gender and climate change focal points from the Caribbean met in Jamaica to discuss the topic of Integrating Gender Considerations in the National Adaptation Plan (NAP) Process. For many of the participants from Jamaica, Saint Lucia, and Antigua and Barbuda, this was their first time discussing the topic. And yet, by the end of the two-and-a-half-day workshop, the representatives had identified crucial next steps to ensuring their respective adaptation processes were more gender-responsive

But before these pathways could be defined, the participants first developed a shared understanding of climate change and gender issues through a series of activities and dialogues—one of which prompted this very important question. In a workshop with only a handful of male participants, and in a country where women make up the majority of civil service decision makers, is there really a “gender issue”?

It’s a fair question, given that the discussions of gender issues often focus on the need for women’s empowerment. This is unsurprising given the barriers and injustices faced by many women due to traditional social norms and practices. Clearly, overcoming these issues is a critical prerequisite for achieving gender equality and sustainable development.

However, by limiting the conversations to generalizations about women’s particular vulnerabilities, we run the risk of missing the nuance of gender relations and the ways in which it intersects with other marginalization issues, such as race/ethnicity, disability and poverty—all of which influence vulnerability to climate change.

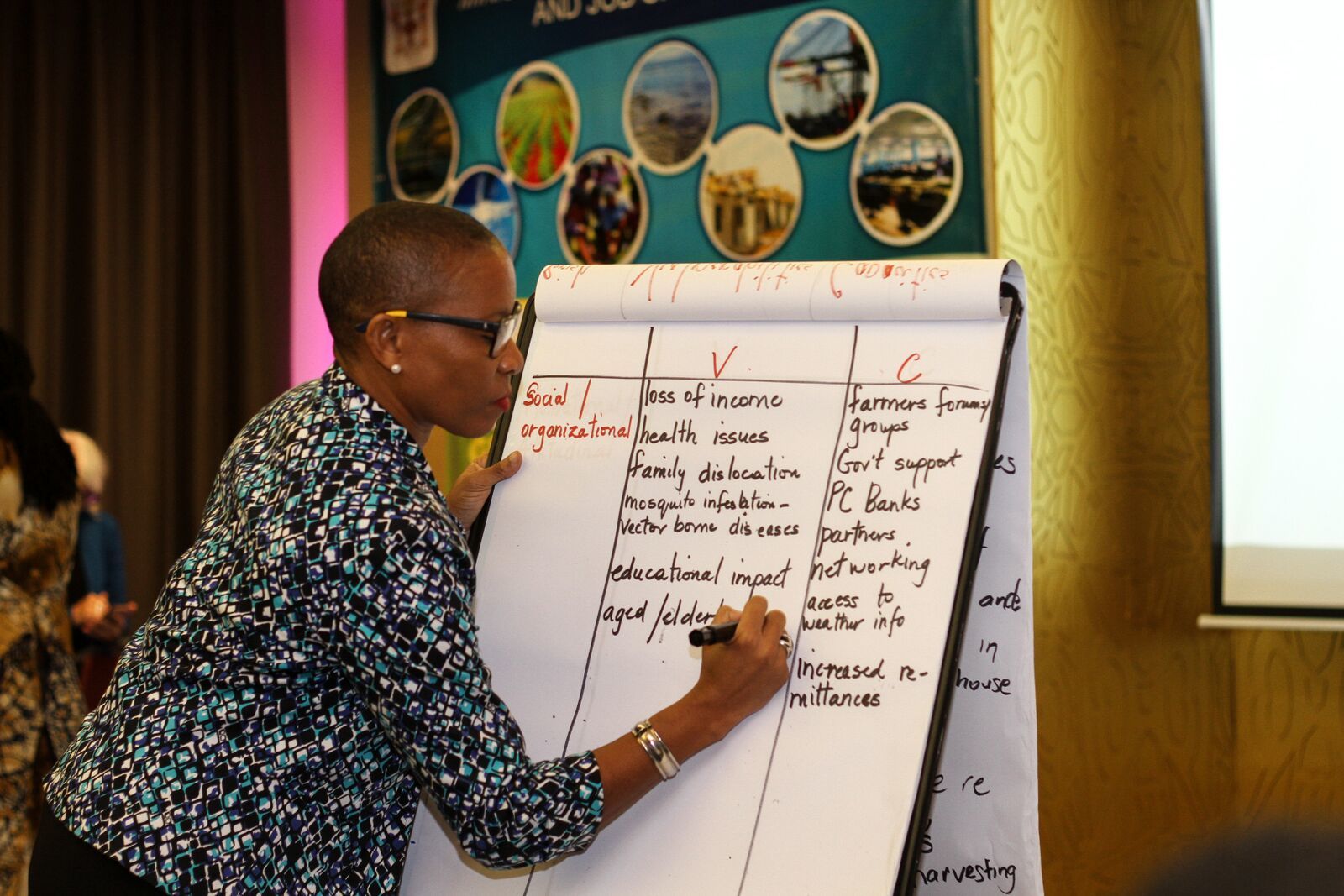

Defining Gender

The nuances of understanding gender were a key topic of discussion for Tonni Brodber, Deputy Representative of UN Women and co-facilitator of the workshop. Brodber first led the participants in defining key terms like gender: the socially constructed attributes and opportunities associated with being male and female and the relationships between them. Brodber also stressed that meaningful gender analysis entails assessing these relationships as well as the capabilities and vulnerabilities of both men and women. And while this does include highlighting the specific vulnerabilities of women, it also means delving into why these exist and identifying in what sectors and situations women or men can act as key agents of change.

Gender Analysis in the Caribbean

"Considering gender does not mean focusing on division, it means acknowledging and appreciating our differences." Wise words from @caribanuck from @UN_Women as we kick off discussions on gender and adaptation planning here in Jamaica. #NAPgenderJAM #NAPgender pic.twitter.com/7JZWwSc68w

— Angie Dazé (@angie_daze) September 18, 2018

According to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics, more women than men attend post-secondary school in Jamaica. This is reflected in the Caribbean more broadly, with girls outperforming boys in standardized tests in primary and secondary school. Despite this performance, these educational achievements are not yet reflected in the labour market or in closing the wage gap. The unemployment rate is still higher for women in Jamaica. And while the Caribbean has the second-highest rate of female entrepreneurship in the world, the majority are still concentrated in small and medium-sized enterprises.

In decision-making processes, women outnumber men in Jamaica in leadership positions in civil service: positions as permanent secretaries, heads of departments and divisions, etc. This was reflected most apparently in the Jamaican workshop, with women outnumbering men 4:1. However, it is important to note that this participation is not the case for local government leaders, councillors, mayors, or government ministers in Jamaica, where men clearly outnumber women. So, while it is clear that women are participating in decision-making processes in the capital cities, it is also apparent that this is not reflective of the situation everywhere—most notably in local and regional governance structures.

What Does This Mean for the NAP Process?

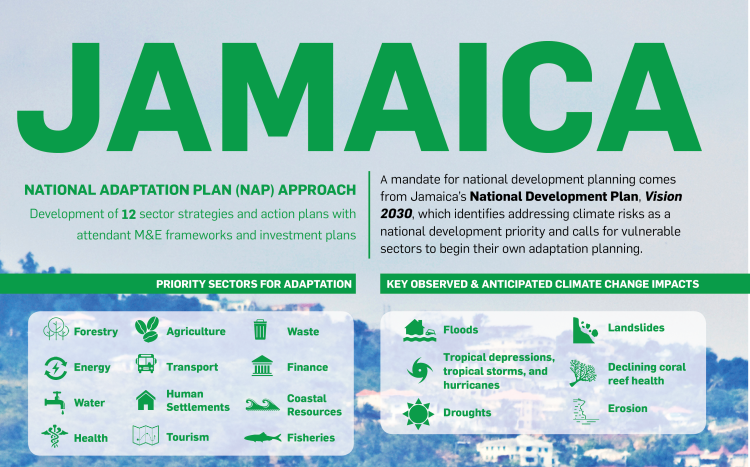

Ayesha Constable of the Ministry of Economic Growth and Job Creation next went through Jamaica’s NAP process, along with Principal Director of the Climate Change Division UnaMay Gordon. Jamaica is taking a sectoral approach to its NAP process, which involves integrating climate change in planning across 12 identified climate-vulnerable sectors, including tourism and health.

So honored to have been able to work with the awesome team of @clarechurch @angie_daze @gemgord on #NAPGenderJAM & heartened by the positive feedback from all the participants. Heading home tired but satisfied #teamwork #progressmade #grateful

— Ayesha Constable (@EshaSensei) September 20, 2018

Representatives from each ministry have been identified as climate change focal points, to help guide, mainstream, and integrate adaptation and mitigation policies. Similarly, gender is treated as a cross-cutting issue, with focal points tasked with mainstreaming gender across the work of their respective agencies. In some cases—as was determined throughout the workshop—these gender and climate change focal points had never met. The workshop provided an opportunity for these different actors to learn from each other and to identify opportunities for collaboration, ensuring that the mainstreaming of both climate change adaptation and gender issues are moved forward in a way that is efficient, comprehensive and meaningful. The importance of creating these institutional linkages between gender and climate change actors cannot be overstated.

Looking beyond the government structures, a gender-responsive NAP process requires equitable participation and influence by women and men in adaptation decision making at all levels. At the local level, efforts may be required to ensure that women are employed as agents of change in climate change adaptation actions and initiatives. Men also, however, are essential actors in overcoming discriminatory norms and practices, and getting them on board helps to create a space to challenge entrenched views and open up dialogue. Increased focus on the agency of individual women and men, particularly those in vulnerable groups and communities, is needed to ensure that adaptation planning processes realize the principles of participation, gender-responsiveness and “leaving no one behind,” as outlined in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Angie Dazé, Associate for the NAP Global Network and co-facilitator of the September workshop, noted that having a diverse mix of women and men at the table will help to ensure that gender differences in adaptation needs, opportunities and capacities are understood and accounted for in NAP processes, and that the benefits of adaptation investments are equitably shared.

Next Steps

This workshop was proposed almost one year ago at the Targeted Topics Forum (TTF) in Fiji as part of the ongoing process of integrating gender considerations into Jamaica’s NAP process. During the TTF gender day in February 2018, Jamaican representatives highlighted the need to bring their climate change and gender focal points together to spark this dialogue. Since then, the Ministry of Economic Growth and Job Creation has worked to deliver this dialogue as well as to initiate a gender analysis of the Jamaican climate policy.

For UnaMay Gordon, Principal Director of the Climate Change Division in the Ministry of Economic Growth and Job Creation, this dialogue and analysis is foundational. “It’s not just about putting women on the agenda,” she said at the Jamaica workshop. “It’s also about recognizing that putting gender considerations into development and adaptation planning is a matter of growth and dialogue.”

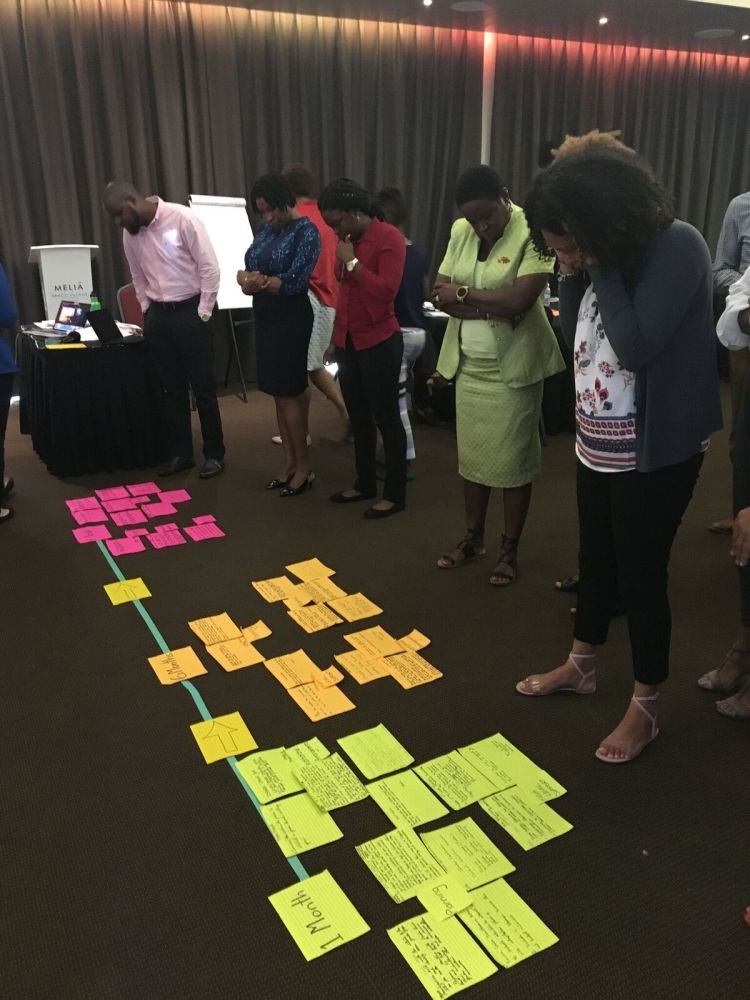

Teams of gender and climate change focal points from different institutions next worked together to identify entry points in upcoming policy and planning processes to address climate change and gender in an integrated manner. Based on this, they identified actions they can take over the next year to move this agenda forward. In many cases, raising senior management awareness of the links between gender and climate change was identified as an essential next step. Capacity building, both for government actors and for other stakeholders, is needed to create an enabling environment for gender-responsive adaptation planning and implementation. In many agencies, there are near-term opportunities to apply the gender and climate change lenses in policy development and planning, providing openings to concretize the knowledge and approaches gained through the workshop. Ongoing dialogue between gender and climate actors was also highlighted as an important element in ensuring integrated approaches.

The opportunity to re-imagine where we are, where we want to go and how do we get there #Talanoa #NAPgenderJAM #Climatechange @CcdJamaica @kerrie_kat @Petchary @EshaSensei pic.twitter.com/ADL277B4wp

— UnaMay Gordon (@gemgord) September 19, 2018

Conclusions

“Do we even have a gender issue here?”

Despite a room filled with women in a country where female participation in decision-making processes in civil service is high, it is essential to note that the scope of gender issues extend beyond a discussion of women and beyond a discussion of vulnerabilities. Assessing the nuances of these gender issues includes an understanding of the intersectionality of gender identities, the relationships between men and women, and the differences in adaptation opportunities and capacities. Furthermore, it requires an understanding that gender dynamics are not static and that adaptation is an ongoing, flexible process that requires iterative development and implementation.

This workshop in Jamaica took a deep dive into these issues, identifying next steps in integrating these gender considerations into adaptation planning processes. An understanding of these differences, relations and next steps is critical to ensuring the successful integration of gender in NAP processes in Jamaica, the Caribbean and beyond.

Any opinions stated in this blog post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policies or opinions of the NAP Global Network, its funders, or Network participants.