Thriving in Dry Times

How Kenyan communities are working toward drought-resilient livelihoods through the national adaptation plan process

Kenya has been enduring severe drought since 2016.

In recent years, rain in Kenya has often come in the form of intense rainfalls that give rise to additional problems—flash flooding and desert locust outbreaks—rather than providing relief. The drought years have led to an estimated 4.2 million Kenyans in need of humanitarian assistance between 2019 and 2022.

As the climate crisis escalates, Kenyans are taking action to adapt to the impacts of climate change.

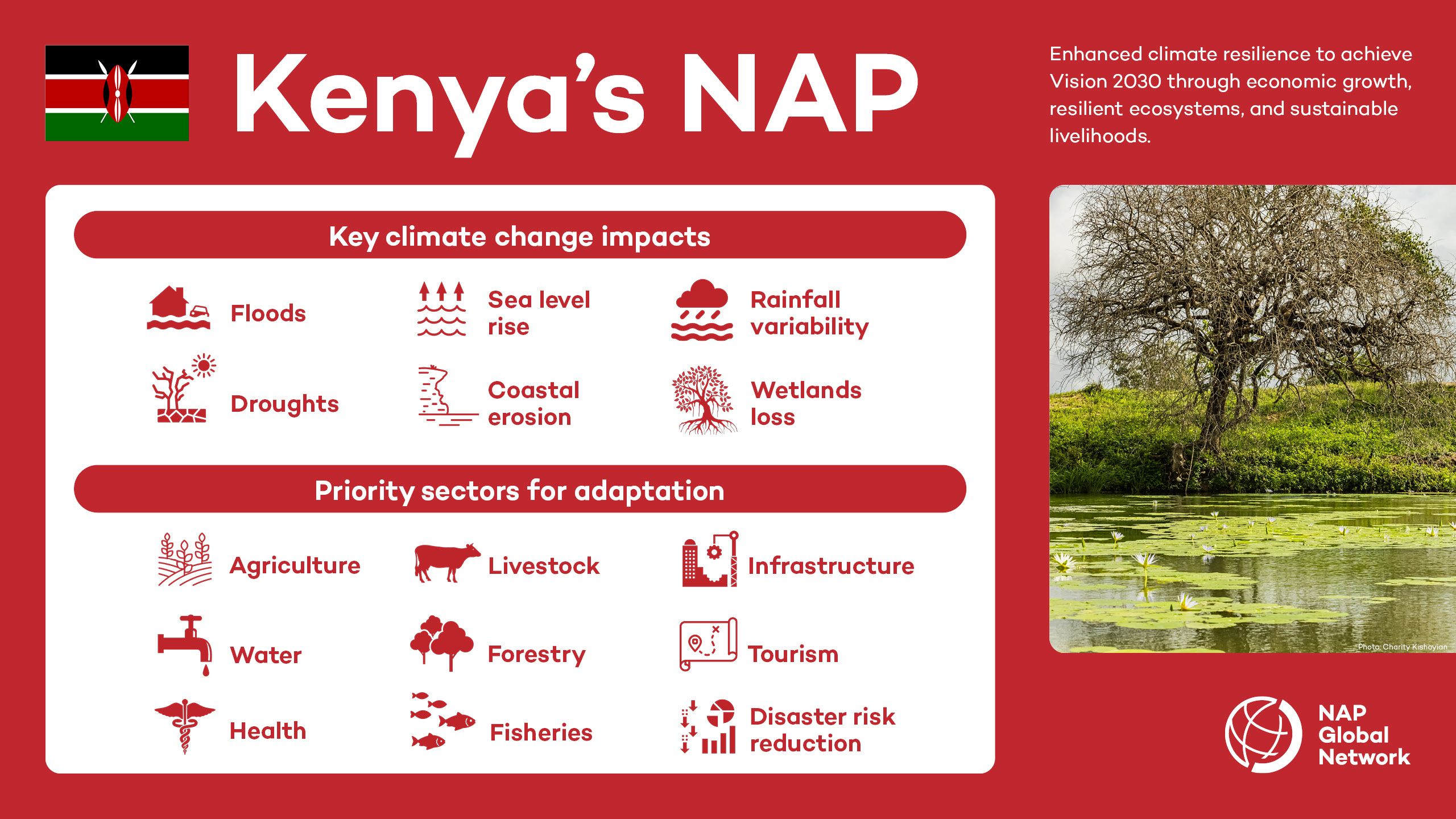

In 2015, the Kenyan government launched the country’s first national adaptation plan (NAP), which set out a vision for building a climate-resilient future. The NAP is delivered through 5-year National Climate Change Action Plans (NCCAPs), with recent plans including priority adaptation actions that aim to reduce risks from drought, increase food security, and ensure access to water. Kenyan communities have an established track record on implementing measures to adapt to climate risk, including drought. Under the NAP process, the country is taking a coordinated approach to scaling up adaptation efforts and initiatives to address vulnerability and build resilience to climate change.

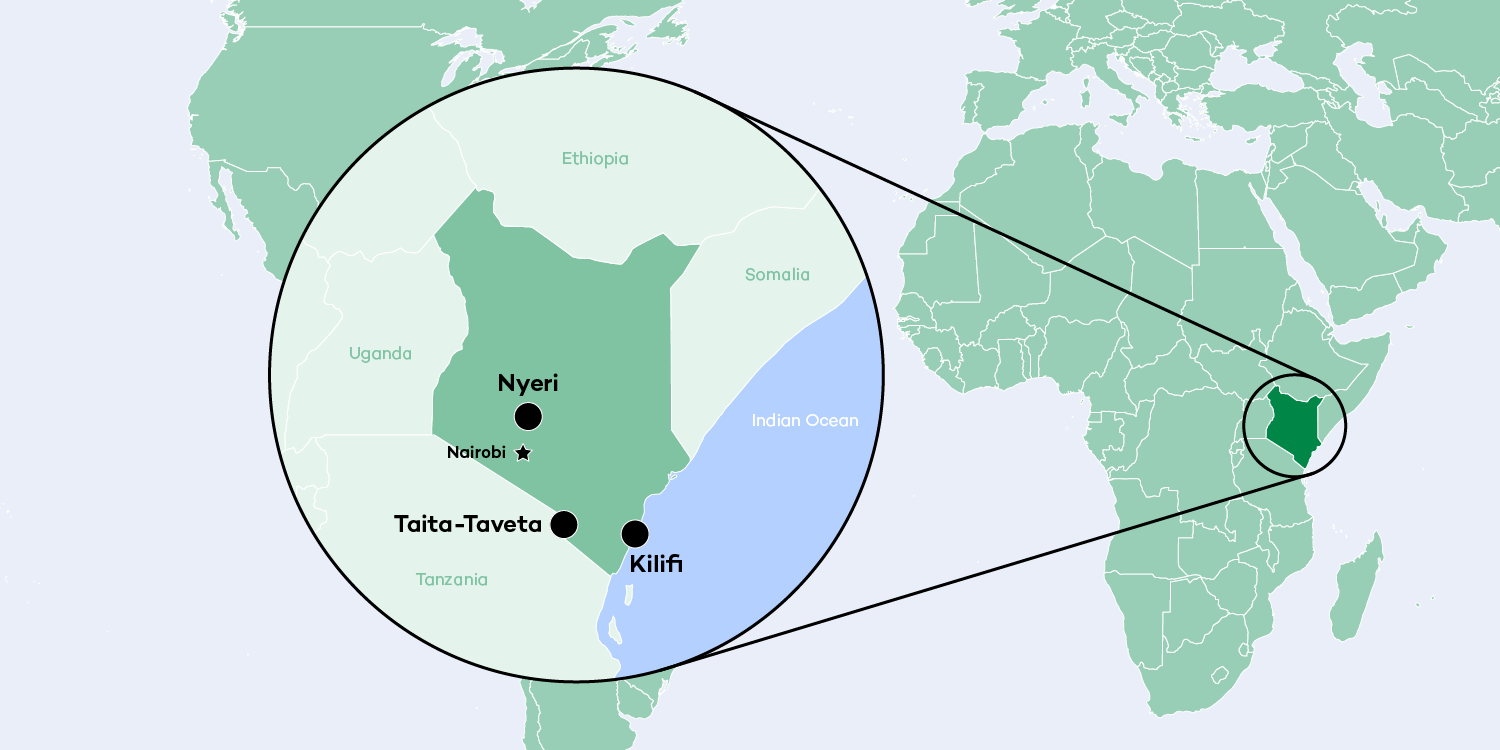

This article shares stories of how Kenyans are implementing adaptation, sharing the progress, challenges, and aspirations of communities as they adapt to the impacts of climate change under the NAP process.

Man bicycling over the Njoro Kubwa Canal. Photo: Charity Kishoyian

Man bicycling over the Njoro Kubwa Canal. Photo: Charity Kishoyian

A woman herding cattle on the Njoro Kubwa Canal. Photo: Charity Kishoyian

A woman herding cattle on the Njoro Kubwa Canal. Photo: Charity Kishoyian

Local boys enjoy a daytime swim, jumping from the top of one canal gate that is used to control water flowing in farms to avoid flooding during heavy rainfall. Photo: Charity Kishoyian

Local boys enjoy a daytime swim, jumping from the top of one canal gate that is used to control water flowing in farms to avoid flooding during heavy rainfall. Photo: Charity Kishoyian

A cracked canal wall as a result of high water pressure flowing during heavy rain. Photo: Charity Kishoyian

A cracked canal wall as a result of high water pressure flowing during heavy rain. Photo: Charity Kishoyian

Restoring the Njoro Kubwa Canal in Taita–Taveta

Njoro Kubwa Canal is a 12-kilometre irrigation canal in Taveta, Taita–Taveta County. Originally built in 2007, the canal transformed the lives of residents in the area, turning a semi-arid area into one of the most fertile regions in the country. Between 40,000 and 50,000 households rely on the canal for farming, boosting the local economy and making Taveta a rich food-producing region.

However, in recent years, the canal fell into disrepair. Cracks in some of the constructed canal walls were leading to water loss, reduced water flow, and blockages within the canal.

To address these and other challenges, the Kenya Climate Smart Agriculture Project (KCSAP) 2017–2023 was implemented by the Kenyan government through a World Bank concessional loan. It is a flagship national project for improving food security and agriculture.

Under the KCSAP, the government invested KES 11 million (USD 75,000) in 2019 to restore the Njoro Kubwa Canal. The rehabilitation works improved the resilience of the canal to extreme rainfall events while ensuring the community continued to have access to water for irrigation and household use.

The canal restoration is an important example of the progress made under the NAP process toward the NCCAP’s priority action on food security to “increase crop productivity through improved irrigation.”

Ruth Benedict's farm grows tomatoes, beans, maize and bananas, which she sells to Mombasa and to the residents of Taveta. Photo: Charity Kishoyian

Ruth Benedict's farm grows tomatoes, beans, maize and bananas, which she sells to Mombasa and to the residents of Taveta. Photo: Charity Kishoyian

Local farmer Ruth Benedict welcomed the Njoro Kubwa Canal restoration. She has farmed in the region for 25 years, growing tomatoes, beans, maize and bananas, which she sells to Mombasa and to the residents of Taveta. Photo: Charity Kishoyian

Local farmer Ruth Benedict welcomed the Njoro Kubwa Canal restoration. She has farmed in the region for 25 years, growing tomatoes, beans, maize and bananas, which she sells to Mombasa and to the residents of Taveta. Photo: Charity Kishoyian

Salim Rashid grows rice, yams, sugarcane and bananas on his farm in Kitobo B. He says that the canal has helped with irrigation, making his crops less depending on rainfall. However, during periods of high rainfall, Rashid and neighbors have experienced their crops being flooded. Photo: Charity Kishoyian

Salim Rashid grows rice, yams, sugarcane and bananas on his farm in Kitobo B. He says that the canal has helped with irrigation, making his crops less depending on rainfall. However, during periods of high rainfall, Rashid and neighbors have experienced their crops being flooded. Photo: Charity Kishoyian

Salim Rashid grows rice, yams, sugarcane and bananas on his farm in Kitobo B. He says that the canal has helped with irrigation, making his crops less depending on rainfall. However, during periods of high rainfall, Rashid and neighbors have experienced their crops being flooded. Photo: Charity Kishoyian

Salim Rashid grows rice, yams, sugarcane and bananas on his farm in Kitobo B. He says that the canal has helped with irrigation, making his crops less depending on rainfall. However, during periods of high rainfall, Rashid and neighbors have experienced their crops being flooded. Photo: Charity Kishoyian

Christopher Kioko is a young farmer whose 2-acre farm benefits from the canal. Prior to farming, his family cut wood to produce charcoal. Kioko’s farm now grows bananas, beans, eggplant, cucumber and maize. When canal water levels are low, the water is unable to reach their crops. Photo: Charity Kishoyian, Irene Saitoti

Christopher Kioko is a young farmer whose 2-acre farm benefits from the canal. Prior to farming, his family cut wood to produce charcoal. Kioko’s farm now grows bananas, beans, eggplant, cucumber and maize. When canal water levels are low, the water is unable to reach their crops. Photo: Charity Kishoyian, Irene Saitoti

Faith Isaac is another community member who has benefited from the Njoro Kubwa Canal. She has been a farmer for about seven years and owns half an acre of land where she plants bananas and ‘gogo’ (also known as garden eggs). Photo: Irene Saitoti.

Faith Isaac is another community member who has benefited from the Njoro Kubwa Canal. She has been a farmer for about seven years and owns half an acre of land where she plants bananas and ‘gogo’ (also known as garden eggs). Photo: Irene Saitoti.

Faith Isaac is another community member who has benefited from the Njoro Kubwa Canal. She has been a farmer for about seven years and owns half an acre of land where she plants bananas and ‘gogo’ (also known as garden eggs). Photo: Irene Saitoti.

Faith Isaac is another community member who has benefited from the Njoro Kubwa Canal. She has been a farmer for about seven years and owns half an acre of land where she plants bananas and ‘gogo’ (also known as garden eggs). Photo: Irene Saitoti.

Cattle, Dairy, and Aquaculture in Nyeri

John Karanja Wahome, Chairman of Aberdare Welfare Group, prepares feed for his cows. Photo: Catherine Lengipa Lengip

John Karanja Wahome, Chairman of Aberdare Welfare Group, prepares feed for his cows. Photo: Catherine Lengipa Lengip

In Nyeri County, the KCSAP provided critical support toward the NAP’s and NCCAP’s objectives to support small-scale subsistence farmers, including livestock farmers, to improve food security.

The Aberdare Welfare group accessed support under KCSAP for training on approaches—like adopting a “Zero Grazing” method where grass is cut fresh and fed to cattle. The new approaches enable farmers to keep livestock when drought destroys pastures, while increasing their cattle’s production of milk—the group saw production grow from 6 litres per day to 20 litres per day. The training also provided methods for keeping their cattle healthier, for using manure to boost crop yields, and for using manure to produce biogas as an alternative source of energy in a community that had relied on firewood, often illegally cut from local forests. The NCCAP 2018–2022 aimed to encourage 80,000 households to adopt biogas technology as a climate-smart agricultural approach that helps combat deforestation (a further priority under the NAP process). The Nyeri projects are helping to achieve this goal.

Members of the Nyeri-based Kiagi Self Help Group also accessed KCSAP funding to create a biogas unit. Biogas is now providing community members with an alternative to using illegally cut firewood for fuel. The use of biogas has also reduced indoor pollution that presents a health risks to the families. While modest, this achievement will add to other similar initiatives across Kenya in the achievement of the adaptation targets under the NAP and NCCAP. They have also accessed training on farming practices like crop rotation and dam building to harvest water to deal with inconsistent rainfall.

Miriam Wothaya from the Kiagi Self Help Group checking her bio-gas chamber and cooking using bio-gas, an alternative to firewood. Photo: Esther Tinayo

Miriam Wothaya from the Kiagi Self Help Group checking her bio-gas chamber and cooking using bio-gas, an alternative to firewood. Photo: Esther Tinayo

Rose Migure has built a water pan for her cattle and farm needs. Photo: Esther Tinayo

Rose Migure has built a water pan for her cattle and farm needs. Photo: Esther Tinayo

Rose Migure has built a water pan for her cattle and farm needs. Photo: Esther Tinayo

Rose Migure has built a water pan for her cattle and farm needs. Photo: Esther Tinayo

Rose Migure has built a water pan for her cattle and farm needs. Photo: Esther Tinayo

Rose Migure has built a water pan for her cattle and farm needs. Photo: Esther Tinayo

The Gakawa Integrated Group produces feed and mineral salts for cattle. In 2021, they accessed KCSAP funds to buy machinery, including a pelletizer, mixer, and mill to make pellets from grass—but soon ran into production issues due to the drought, with raw materials becoming more expensive and of poor quality. Despite the challenges, the Gakawa Integrated Group has managed to produce an impressive 45 tonnes of feed since January 2022 and is working to certify its products to start selling to the market.

Inland Aquaculture in Nyeri

Kenya’s NAP includes fisheries as a priority sector, aiming to expand both inland and coastal fisheries, highlighting inland fisheries through aquaculture is one approach for Kenyan communities to diversify their livelihoods and boost food security.

In 2018, Jane Kimondo accessed support to start an aquaculture business from the Aquaculture Business Development Programme (ABDP) 2017-2026 implemented by International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) and Kenya’s Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Fisheries and Co-operatives (MALF&C).

Jane lives in Karioba village, Kihatha, Nyeri County, where an aquaculture program had previously been attempted in 2012 without success. The new program, however, is showing promising results. Through ABDP support, she was able to secure a pod liner, 1000 fingerlings, a cover net and four bags of fish feed.

Jane’s first sale was 20kg of tilapia and 60kg of catfish, which she sold directly to customers. She can now comfortably run her business and support her family.

The Kenyan government reports having helped establish over 11,000 fishponds by 2020, contributing to the NCCAP goal to “improve productivity in the fisheries through implementation of [climate-smart agriculture] interventions.”

Portrait of Jane Kimondo. Photo: Esther Tinayo

Portrait of Jane Kimondo. Photo: Esther Tinayo

Diversifying Livelihoods in Kilifi

Jiinue Self Help Group’s Goat Initiative

Diversification of livelihoods is a key adaptation priority in Kenya, with the NCCAP setting out a goal of supporting over half a million households to adopt diversified livelihoods and strengthening food security. The NAP, as the overarching framework for adaptation, promotes livelihood diversification for vulnerable groups in order to reduce rural–urban migration while enhancing access to the youth and women enterprise funds and establishing affordable and accessible credit lines for the urban and rural poor, youth, and other vulnerable groups. Two examples from Kilifi demonstrate how community groups are making climate-resilient livelihoods a reality.

In 2020, Kenya’s National Drought Management Authority (NDMA) funded a community-based initiative put forward by the Jiinue Self Help Group in Kilifi County to diversify livelihoods by promoting goat farming. Prior to goat farming, many community members made a living from cutting down trees to burn for charcoal, resulting in a significant loss of tree coverage in the area and increasing the community’s vulnerability to drought.

The NDMA—through the Asset Creation Programme that was supported by the World Food Programme and contributed to the implementation of the Government of Kenya’s Ending Drought Emergencies program—provided each of the Jiinue Self Help Group members with five goats (four “nanny goats” and one buck) to help the community begin shifting their livelihoods from gathering charcoal to goat farming. Selling goats, which could be sold for between KES 7,000 and KES 12,000 (approximately USD 50–80), offers a new source of income to help families pay for food, school fees, and other expenses.

But shifting to farming goats has also brought challenges. Many goats died during the severe drought in 2021, and several more died from pneumonia and snake bites. Several were stolen due to desperation in the community driven by the drought.

Recognizing that the benefits of goat farming could be threatened if drought continues or worsens, the community has identified further steps to diversify local livelihoods. They have proposed accessing future support to raise a drought-resilient breed of chickens and dairy breeds of goats and to build a dam to improve access to clean water.

Kakahindi Wakimwele, a member of the Jiinue Self Help Group. Photo: Charity Kishoyian

Kakahindi Wakimwele, a member of the Jiinue Self Help Group. Photo: Charity Kishoyian

Kakahindi Wakimwele tending to her goats. It has been raining for the previous 3 months, and the landscape in the area has greatly improved, meaning food for her livestock. Photo: Charity Kishoyian

Kakahindi Wakimwele tending to her goats. It has been raining for the previous 3 months, and the landscape in the area has greatly improved, meaning food for her livestock. Photo: Charity Kishoyian

Karisa Masha, Fiki chairman of Jiinue Self Help Group, now has a herd of about 70 goats. Photo: Irene Saitoti

Karisa Masha, Fiki chairman of Jiinue Self Help Group, now has a herd of about 70 goats. Photo: Irene Saitoti

Karisa Masha, Fiki chairman of Jiinue Self Help Group, now has a herd of about 70 goats. Photo: Irene Saitoti

Karisa Masha, Fiki chairman of Jiinue Self Help Group, now has a herd of about 70 goats. Photo: Irene Saitoti

Ufanisi Youth Group’s Chicken Initiative

The Ufanisi Youth Group originally had only five members. After participating in a training on financial stability offered by the NDMA in 2018, the group was asked by the NDMA to propose a livelihood diversification project. It requested support to take on broiler farming to diversify its small farms. By shifting to drought-resistant poultry breeds, the group members built resilience by creating an alternate income stream. They received 500 chicks and, through a livestock officer’s guidance, managed to sell 98% of the broilers.

Having grown to 20 members when they received the broilers from the NDMA, the Ufanisi Youth Group agreed to split the profits, with 50% going to the group savings and 50% going to group members. In 2020, they decided to start a “Savings and Credit Cooperative Organization or Society” (SACCO) to pool resources and make loans available to members, partnering with 15 groups to form the “Mnarani Tupo SACCO.” The SACCO grew steadily and, by 2021, had a total of 2000 members with a total deposit of KES 8.5 million (approximately USD 60,000).

Though occasionally faced with challenges like low prices and difficulty accessing markets, the group members have achieved greater sources of income and gained knowledge on managing businesses profitably. In addition to raising poultry, Ufanisi Youth Group members also farm crops to sustain themselves and their families.

In its NCCAP progress report for 2019–2020, the Kenyan government reports that 290,000 households had received support to diversify such enterprises for sustainable livelihoods and food security—with enterprises including “indigenous poultry, dairy goats, dairy intensification, tissue culture in banana production, and pasture seeds, among others.”

Nickson Tele in his chicken shed. The Ufanisi Youth Group allocated 25 broiler chicks to each member. Photo: Charity Kishoyian.

Nickson Tele in his chicken shed. The Ufanisi Youth Group allocated 25 broiler chicks to each member. Photo: Charity Kishoyian.

Nickson Tele in his chicken shed. The Ufanisi Youth Group allocated 25 broiler chicks to each member. Photo: Charity Kishoyian.

Nickson Tele in his chicken shed. The Ufanisi Youth Group allocated 25 broiler chicks to each member. Photo: Charity Kishoyian.

The Thigi Nyumba Kumi Self Help Group accessed a KCSAP grant in late 2021 invest in an incubator machine, as well as chicklings, sheep, and kitchen garden seeds for members. The group members can breed more chicklings with the incubator and sell them in the market. Agnes Kiruru, Chairlady Nyumba Kumi Self Help Group, and her husband preparing food for their chickens. Group members also harvest kale to supplement poultry farming. Photo: Catherine Lengipa Lengip

The Thigi Nyumba Kumi Self Help Group accessed a KCSAP grant in late 2021 invest in an incubator machine, as well as chicklings, sheep, and kitchen garden seeds for members. The group members can breed more chicklings with the incubator and sell them in the market. Agnes Kiruru, Chairlady Nyumba Kumi Self Help Group, and her husband preparing food for their chickens. Group members also harvest kale to supplement poultry farming. Photo: Catherine Lengipa Lengip

The Thigi Nyumba Kumi Self Help Group accessed a KCSAP grant in late 2021 invest in an incubator machine, as well as chicklings, sheep, and kitchen garden seeds for members. The group members can breed more chicklings with the incubator and sell them in the market. Agnes Kiruru, Chairlady Nyumba Kumi Self Help Group, and her husband preparing food for their chickens. Group members also harvest kale to supplement poultry farming. Photo: Catherine Lengipa Lengip

The Thigi Nyumba Kumi Self Help Group accessed a KCSAP grant in late 2021 invest in an incubator machine, as well as chicklings, sheep, and kitchen garden seeds for members. The group members can breed more chicklings with the incubator and sell them in the market. Agnes Kiruru, Chairlady Nyumba Kumi Self Help Group, and her husband preparing food for their chickens. Group members also harvest kale to supplement poultry farming. Photo: Catherine Lengipa Lengip

The Thigi Nyumba Kumi Self Help Group accessed a KCSAP grant in late 2021 invest in an incubator machine, as well as chicklings, sheep, and kitchen garden seeds for members. The group members can breed more chicklings with the incubator and sell them in the market. Agnes Kiruru, Chairlady Nyumba Kumi Self Help Group, and her husband preparing food for their chickens. Group members also harvest kale to supplement poultry farming. Photo: Catherine Lengipa Lengip

The Thigi Nyumba Kumi Self Help Group accessed a KCSAP grant in late 2021 invest in an incubator machine, as well as chicklings, sheep, and kitchen garden seeds for members. The group members can breed more chicklings with the incubator and sell them in the market. Agnes Kiruru, Chairlady Nyumba Kumi Self Help Group, and her husband preparing food for their chickens. Group members also harvest kale to supplement poultry farming. Photo: Catherine Lengipa Lengip

The Thigi Nyumba Kumi Self Help Group accessed a KCSAP grant in late 2021 invest in an incubator machine, as well as chicklings, sheep, and kitchen garden seeds for members. The group members can breed more chicklings with the incubator and sell them in the market. Agnes Kiruru, Chairlady Nyumba Kumi Self Help Group, and her husband preparing food for their chickens. Group members also harvest kale to supplement poultry farming. Photo: Esther Tinayo

The Thigi Nyumba Kumi Self Help Group accessed a KCSAP grant in late 2021 invest in an incubator machine, as well as chicklings, sheep, and kitchen garden seeds for members. The group members can breed more chicklings with the incubator and sell them in the market. Agnes Kiruru, Chairlady Nyumba Kumi Self Help Group, and her husband preparing food for their chickens. Group members also harvest kale to supplement poultry farming. Photo: Esther Tinayo

The Thigi Nyumba Kumi Self Help Group accessed a KCSAP grant in late 2021 invest in an incubator machine, as well as chicklings, sheep, and kitchen garden seeds for members. The group members can breed more chicklings with the incubator and sell them in the market. Agnes Kiruru, Chairlady Nyumba Kumi Self Help Group, and her husband preparing food for their chickens. Group members also harvest kale to supplement poultry farming. Photo: Esther Tinayo

The Thigi Nyumba Kumi Self Help Group accessed a KCSAP grant in late 2021 invest in an incubator machine, as well as chicklings, sheep, and kitchen garden seeds for members. The group members can breed more chicklings with the incubator and sell them in the market. Agnes Kiruru, Chairlady Nyumba Kumi Self Help Group, and her husband preparing food for their chickens. Group members also harvest kale to supplement poultry farming. Photo: Esther Tinayo

The Thigi Nyumba Kumi Self Help Group accessed a KCSAP grant in late 2021 invest in an incubator machine, as well as chicklings, sheep, and kitchen garden seeds for members. The group members can breed more chicklings with the incubator and sell them in the market. Agnes Kiruru, Chairlady Nyumba Kumi Self Help Group, and her husband preparing food for their chickens. Group members also harvest kale to supplement poultry farming. Photo: Esther Tinayo

The Thigi Nyumba Kumi Self Help Group accessed a KCSAP grant in late 2021 invest in an incubator machine, as well as chicklings, sheep, and kitchen garden seeds for members. The group members can breed more chicklings with the incubator and sell them in the market. Agnes Kiruru, Chairlady Nyumba Kumi Self Help Group, and her husband preparing food for their chickens. Group members also harvest kale to supplement poultry farming. Photo: Esther Tinayo

Water Pans in Shomela and Ndigiria, Kilifi County

Water pans are an important tool in Kenya’s toolkit as a water-scarce country fighting drought.

Water pans are a low-cost and relatively simple technology that can help communities—especially in semi-arid regions—to cope with climate change. They help communities harvest water for households as well as livestock and agricultural use and can play a key role in achieving the NAP’s and NCCAP’s goals on water availability and food security. They can also contribute to the NCCAP priority to “increase gender-responsive affordable water harvesting” by reducing the distances that women and youth need to travel for water.

Agnes, a community member who lives near the Ndigiria water pan that has been in place for several decades, explains its long-time importance to the community: “I was born, raised, and married in this village. I live here with my family. I am a maize farmer, and I also have a few chickens. We’ve depended on this water pan for farming and the household all our lives.”

Portrait of Agnes. Photo: Charity Kishoyian

Portrait of Agnes. Photo: Charity Kishoyian

Riziki Katama lives in neighbouring Shomela, where a water pan was built in 2020. The pan has benefited Shomela, as they previously had to fetch water from distant locations. Photo: Charity Kishoyian

Riziki Katama lives in neighbouring Shomela, where a water pan was built in 2020. The pan has benefited Shomela, as they previously had to fetch water from distant locations. Photo: Charity Kishoyian

However, water pans require ongoing support to avoid the negative impacts for the community if they fail.

“Sometimes the water dries up, and we can’t farm. It becomes a big problem around here to get water for drinking; children want to eat and go to school, but many people suffer a lot without water in this pan. I have benefited a lot, especially living near the water pan. I harvest and sell maize twice a year, but when the water pan dries, we won’t have any other source of income,” says Agnes.

In October 2022, the drought situation in Kenya worsened and affected 4.35 million Kenyans. Water pans across the Kilifi region were among many that suffered; not only drying up but also suffering infrastructural damage due to the drought, which worsened once the rains finally came. The Kenyan government has emphasized the importance of these water pans in helping Kenya achieve its adaptation goals, reporting in 2019–2020 the “annual [arid and semi-arid lands’] water harvesting and storage increased by 25%” through small dams and water pans.” The government reports that approximately 129 institutions and 196,262 households developed or strengthened water harvesting structures like water pans across Kenya, including in Ndigiria and Shomela in Kilifi county.

James Kalume, Chief Chairperson of the Ndigiria Water Pan, and Chengo Wanje Chile, Assistant Chairperson, also recount having faced challenges: “By bad luck, it rained heavily, and the water pan filled and broke along the edge on one side, and the water drained out. The water pan could no longer hold much water for long, and crops started dying ... after it broke, the edges no longer had a water source.” They emphasize that securing and maintaining the water pan requires support from government and funders. The communities also need technical support in terms of ensuring climate proofing of infrastructure like dams. This calls for the engagement of technical experts.

James Kalume, Chief, Ndigiria Water Pan Chairperson, and Chengo Wanje Chile, Ndigiria Water Pan Assistant Chairperson. Photo: Irene Saitoti

James Kalume, Chief, Ndigiria Water Pan Chairperson, and Chengo Wanje Chile, Ndigiria Water Pan Assistant Chairperson. Photo: Irene Saitoti

Scaling Up Climate-Resilient Development Through the NAP Process

Kenyan communities are responding to the hardships of drought through an impressive and diverse range of strategies to establish climate-resilient livelihoods—from restoring a vital canal in Taveta, to diversifying livelihoods with poultry, goats, and aquaculture in Nyeri and Kilifi, these stories profile just some of the efforts underway to build climate resilience.

As climate change risks become worse in coming decades, alongside urgent efforts to cut greenhouse gas emissions globally, it is increasingly urgent to scale up national, county, and community efforts to adapt to climate change. Kenya’s NAP and NCCAP set out adaptation priorities to guide action and face these risks, channeling support to community-driven initiatives to build resilience to climate change.

Credits

Photos and stories by: Charity Kishoyian, Irene Saitoti, Catherine Lengipa Lengip, Esther Tinayo, Claire Metito, Brian Siambi

This photo story builds on Envisioning Resilience, a joint initiative between the NAP Global Network and Lensational. In 2021, this initiative provided seven young Maasai women in Kenya with photography and storytelling training to develop visual stories that capture their experiences of climate change and visions of resilience. The photos were shared with national climate change decision makers to amplify underrepresented women’s voices in adaptation planning processes. The stories presented in this article were collected and prepared by the alumni of this training program.

Edited by: Christian Ledwell

Special thanks to: Thomas Lerenten Lelekoitien and Samuel Muchiri (Climate Change Directorate, Kenya); Lydia Kibandi (Lensational); Deborah Murphy, Orville Grey, David Hoffmann, and Cesar Henrique Arrais (IISD); Paul Ngari; Kakahindi Wakimwele; Karisa Masha; James Kalume; Chengo Wanje Chile; Nickson Tele; Clemence Sidi; Sharlette Dhahabu; Chenga Kirau; Ruth Benedict; Salim Rashid; Christopher Kioko; Faith Isaac; John Karanja Wahome; Miriam Wothaya; Rose Migure; Agnes Kiruru; Jane Kimondo; Riziki Katama; Mzee Chengo Kirau.

© November 2023, International Institute for Sustainable Development

Published by the International Institute for Sustainable Development.

This publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.