From its establishment in 2010, the national adaptation plan (NAP) process was envisioned as participatory. It is well understood that adaptation requires a whole-of-society approach and that the NAP process is an opportunity to bring the pieces together to achieve this. Engagement is an important enabler for the NAP process, helping to ensure that adaptation decision making is informed by diverse perspectives and that the priorities identified are robust and equitable. Civil society actors are key—they bring knowledge, networks, and perspectives that are needed for effective adaptation.

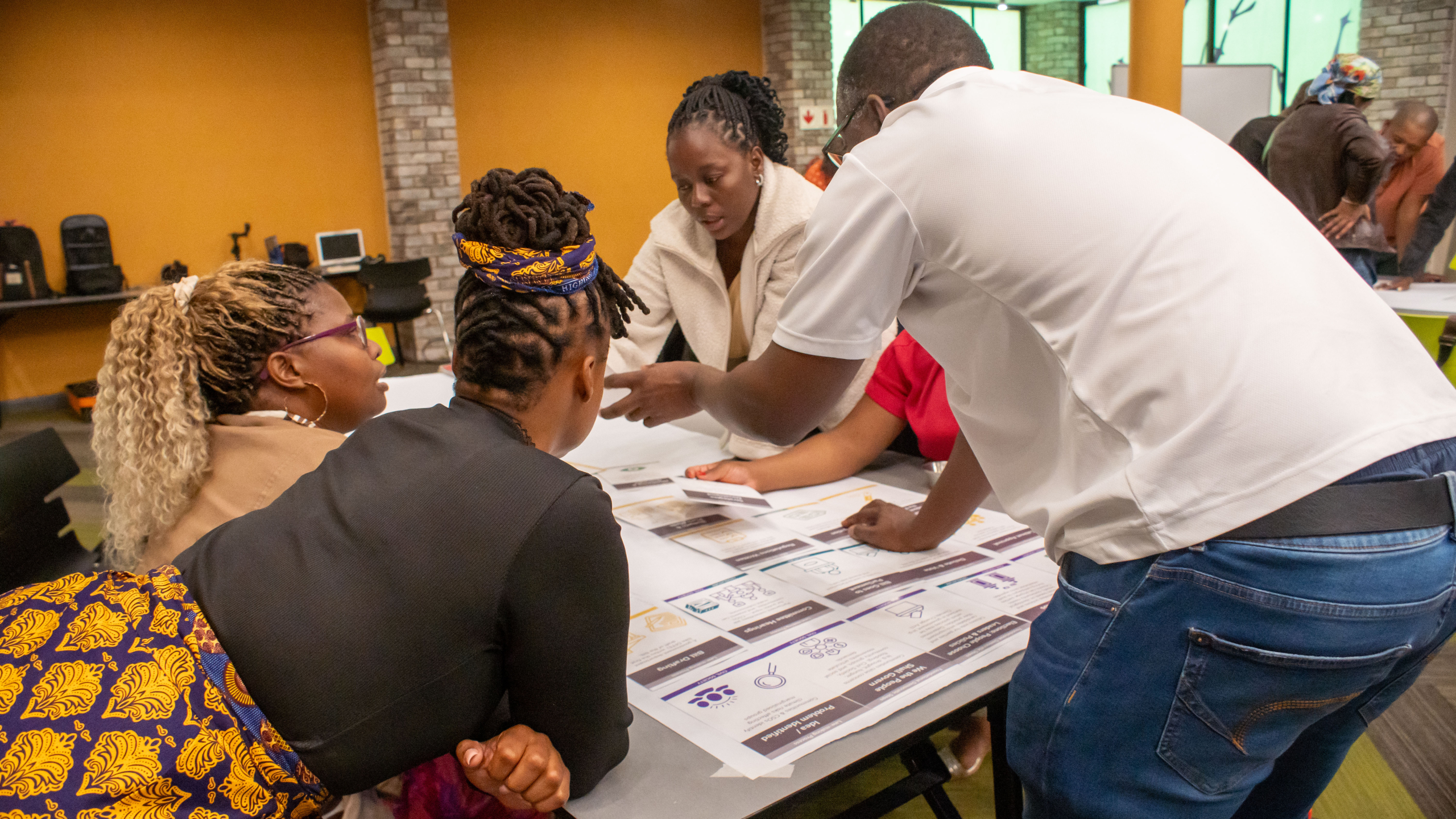

In this analysis, we share some new thinking on civil society engagement in NAP processes. We introduce a set of principles that were co-produced by government and civil society representatives from 11 countries in Africa and the Caribbean during a recent peer-learning event co-hosted by the NAP Global Network and the Government of Namibia.

What do we mean by civil society?

Civil society is sometimes called “the third sector,” distinguishing it from the government and the private sector. Civil society organizations (CSOs) engage in collective action at different levels, with a variety of ways of working and diverse areas of focus. CSOs around the world play key roles in providing services, representing people’s interests, and demanding justice and accountability from power holders. They include community groups, non-governmental organizations, labour unions, and coalitions that are united by a common issue or constituency. As such, CSOs are often embedded within specific populations or communities and aim to generate positive outcomes for them.

Why engage CSOs in the NAP process?

CSOs bring specific knowledge and expertise that is very often grounded in the lived experience of communities. For example, they may have a solid understanding of how climate change impacts affect particular livelihood groups, such as farmers, pastoralists, or fisherfolk. Gender and social justice organizations can help amplify the voices of women and other marginalized groups that are typically underrepresented in adaptation decision making. In many cases, CSOs are already working on adaptation, so engaging them in the NAP process can integrate their experience and perspectives, enhance learning and coordination, and avoid duplicating efforts.

Working with CSOs, particularly at the local level, can lay a foundation of trust and buy-in for adaptation, which is essential for the transition to implementation. Because they are often embedded in communities and integrated in aspects of their work, CSOs can foster innovation and help to address complexity. Importantly, CSOs hold governments to account for the commitments they make and facilitate information-sharing for transparency.

Putting it simply, engaging CSOs in the NAP process can make it more inclusive and effective.

A working set of principles for civil society engagement in the NAP process

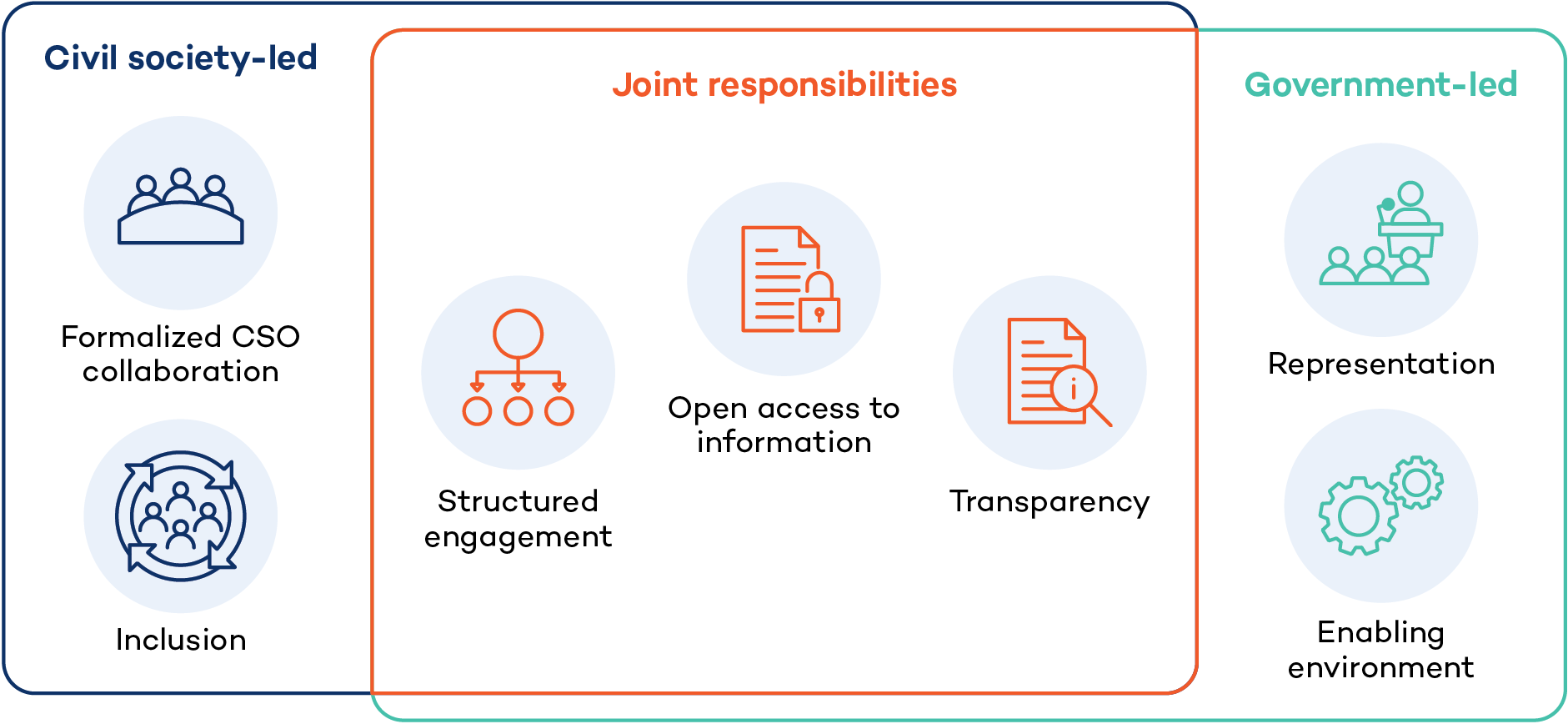

The seven principles presented in Figure 1 were co-produced by a group of government and civil society representatives over the course of a 3-day peer-learning event. These principles capture responsibilities that require joint action by government and CSOs, as well as those that particularly require leadership from either government or civil society. The principles are intended to guide effective engagement of civil society actors throughout all stages of the NAP process: impact, vulnerability, and risk assessment; planning; implementation; and monitoring, evaluation, and learning (MEL). They are shared here as a working version, to be tested and refined over time as NAP processes progress and civil society and government strengthen their collaboration.

The participants defined the principles as follows:

- Structured engagement: Government and civil society establish a formal engagement framework with a defined operational mandate and clear expectations, roles, and responsibilities across the full, iterative NAP process (impact, vulnerability, and risk assessment; planning; implementation; MEL).

- Representation: CSO representatives are included in key decision-making structures of the NAP process (committees, working groups, etc.).

- Formalized CSO collaboration: CSOs organize into formal structures, such as a networks or coalitions, to facilitate engagement in the NAP process, represent diverse and underrepresented civil society voices, mobilize resources for shared priorities, and coordinate collective action through a collaborative process that values all perspectives.

- Inclusion: CSO networks and representatives engaged in the NAP process include diverse actors, particularly community-based organizations and those representing marginalized groups, to enhance relevance, equity, and ownership.

- Enabling environment: Government creates opportunities for a diverse group of CSOs, including those representing marginalized groups, to collaborate on the development, implementation, and MEL of adaptation priorities, ensuring shared ownership through active engagement.

- Open access to information: Government and civil society ensure broad and inclusive access to all relevant data on climate change, MEL, finance, and progress achieved in the implementation of adaptation action.

- Transparency: Open communication of progress, opportunities, challenges, and trade-offs in relation to adaptation fosters mutual accountability among government and civil society.

These are working principles to be tested and refined over time as countries move forward in their NAP processes.

To learn more about how government and civil society actors are working to put these principles into practice, check out our webinar.