Progress takes many forms. How can we transform adaptation planning and decision-making systems to reduce harm and loss in the face of climate change? Here’s what we’ve learned so far.

As the COVID-19 pandemic engulfed much of the world in 2020, climate change proceeded unabated. Indeed, 2020 was another record-breaking year in terms of climate impacts and tied for the warmest year on record. You can take your pick of stories that epitomized this alarming reality. The Arctic burned like never before, with blazes starting earlier, lasting longer, spreading further north, and, to add insult to injury, emitting a record amount of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Closer to the equator, the “hyperactive” 2020 Atlantic hurricane season saw a record number of storms—so many that meteorologists ran out of names for them barely halfway through the season.

These widely reported stories only reinforce what so many communities across the world—especially in least-developed countries and Small Island Developing States—already know: the hard work of preparing for and adjusting to the impacts of climate change must proceed apace. While the COVID-19 crisis has presented challenges in how we do this, it has also elevated the importance of certain adaptation actions. For example, strengthening the resilience of the health sector, scaling up climate-smart agriculture, and expanding water supply and sanitation systems are all investments that empower vulnerable populations to deal with the next crisis, whether climate-related or not.

Moreover, as countries use adaptation actions to promote gender equality and harness the promise of nature-based solutions, they can feed these approaches into resilient recovery efforts. In short, the urgent need to prepare for climate impacts does not have to detract from efforts to manage the pandemic.

Amid the tumult of 2020, we at the National Adaptation Plan (NAP) Global Network Secretariat were taking stock of how our support to more than 40 developing countries was advancing adaptation action. Because our support to a country’s NAP process is tailored to national contexts, it involves a wide range of activities—from the creation of government committees and training of journalists to the adoption of national policies and establishment of systems for tracking progress. What difference do these activities make in strengthening climate resilience?

Over the last year, we have seen firsthand the importance of strengthening systems and capacities that help countries navigate immediate and longer-term crises.

Answering this question wasn’t a self-serving exercise to celebrate the successes of our programming; we genuinely wanted to unpack and categorize the different types of changes we were seeing and share them with the adaptation policy community. What’s more, we felt a sense of urgency around doing this, as it seemed like the “nuts and bolts” contributions of the NAP process—that is, the often incremental but critical work of strengthening the enabling environment for adaptation action and of putting adaptation at the heart of decision making—were being overlooked or underappreciated at an important moment in the global conversation around adaptation. We therefore summarized several stories of change in our new report, Resilience in Action: Five Years of Supporting National Adaptation Plan (NAP) Processes, to make a case for investing in adaptation governance.

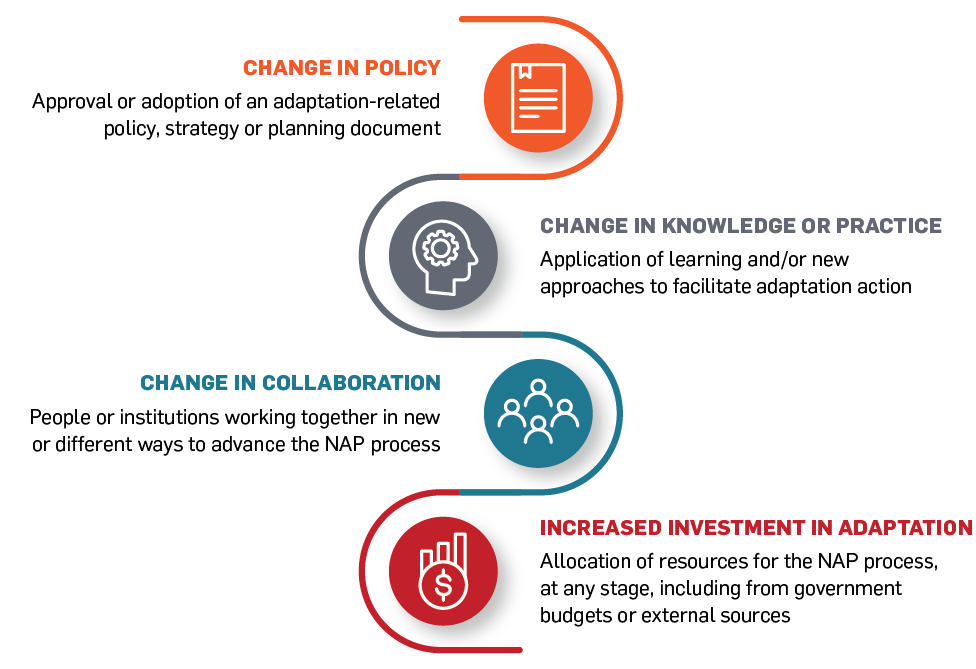

In reviewing what had been achieved across different countries, one key takeaway for us was that progress takes many forms. We identified four mutually reinforcing areas of change to describe the impacts of our work: change in policy, change in knowledge or practice, change in collaboration, and increased investment in adaptation (Figure 1 below). Our belief was that such changes—taken together—lead to the wholesale transformation of planning and decision-making systems needed to reduce harm and loss in the face of climate change.

Change in policy

Changes in policy are, unsurprisingly, the more traditional way of pointing to progress in adaptation planning. Whether it was the approval of Fiji’s first National Adaptation Plan or the development of Saint Lucia’s Sectoral Adaptation Strategy and Action Plan (SASAP) for the Agriculture Sector, the approval of new policies, plans, and strategies represent important mandates and frameworks for meaningful adaptation action. And quality matters. It’s not enough to churn out these documents and communicate them to domestic and international audiences. These documents need to be strategic and actionable, clearly identifying priorities and how they will be addressed, by whom, and in what time frame.

Change in knowledge or practice

Ensuring these changes in policy are not only on paper requires changes in other domains. Changes in knowledge or practice, such as the development and use of Kiribati’s Integrated Vulnerability Assessment database or training South Africa’s government officials in the use of climate science in policy-making, mean that NAP processes target vulnerable communities and ecosystems, informed by the best-available science and Indigenous knowledge. If NAPs are more representative and responsive, they are more likely to lead to meaningful risk reduction.

Change in collaboration

We also learned that NAP processes are as relational as they are technical—how people and jurisdictions work together is crucial for successful adaptation. A series of high-level regional consultations in Ghana were critical to building awareness, support, and momentum for adaptation in the country, just as the creation of Peru’s Indigenous Climate Platform formalized and strengthened the contributions of Indigenous People to the country’s comprehensive management of climate change.

Increased investment in adaptation

Finally, one of the main litmus tests for the NAP process is the extent to which it brings in money for the implementation of adaptation actions. Since much of the support we provided unfolded for between 6 and 36 months, we didn’t expect to see a lot of examples under this category—at least not yet. This is due to one of the biggest lessons we learned: that the transition from planning to implementation is full of many intermediate activities that require skill sets that haven’t traditionally been at the heart of adaptation efforts.

Processes such as developing costing methodologies or financing strategies, integrating adaptation into budgeting processes, exploring public–private partnerships, and, of course, strengthening capacities to access climate finance highlight that the line between identifying and addressing adaptation priorities is neither short nor straight. But we did see important progress being made. Ethiopia’s NAP resource mobilization strategy now provides a clear direction of travel for securing resources for implementation, while Saint Lucia leveraged its aforementioned SASAP to secure USD 10 million from the Adaptation Fund.

These and many other changes brought about through the support of the NAP Global Network should give us hope during this time of uncertainty. Over the last year, we have seen firsthand the importance of strengthening systems and capacities that help countries navigate immediate and longer-term crises. National adaptation plan processes are about doing exactly this. The United Nations states that 125 developing countries have launched these processes, which bodes well for translating adaptation ambition into action. As we head toward the 26th Conference of the Parties (COP 26) and work to accelerate resilience efforts, the NAP Global Network will build on the achievements from its first five years, continuing to support developing countries and striving to place adaptation planning and decision making firmly at the centre of the global climate agenda.

Blog originally appeared on the International Institute for Sustainable Development website.