The impacts of climate change are happening today and will continue to be felt over this century and beyond. Responding effectively to climate change requires urgently cutting our emissions as well as adapting to its impacts. The National Adaptation Plan (NAP) process is an important way that countries can build their resilience to these impacts.

At the NAP Global Network Secretariat, we are often asked—by a range of actors—to explain what the NAP process is and why it’s important. Below are a few of the common questions that we hear.

Have other questions about the NAP process that you would like us to answer? Please get in touch at: info@napglobalnetwork.org

The PDF version is available here.

La version française est disponible ici.

THE BASICS

-

What is the National Adaptation Plan (NAP) process?

The official definition, objectives and guidelines of the NAP process are available via the UNFCCC website.

In simple terms, the NAP process is a strategic process that enables countries to identify and address their medium- and long-term priorities for adapting to climate change.

Led by national governments, the NAP process involves analyzing current and future climate change and assessing vulnerability to its impacts. This provides a basis for identifying and prioritizing adaptation options, implementing these options, and tracking progress and results.

Importantly, the NAP process puts in place the systems and capacities needed to make adaptation an integral part of a country’s development planning, decision making and budgeting while ensuring it is ongoing practice rather than a separate ad hoc exercise.

-

What are the objectives of the NAP process?

Ultimately, the NAP process aims to make people, places, ecosystems, and economies more resilient to the impacts of climate change.

The NAP process also strives to make adaptation part of standard development practice, where adaptation needs are embedded in how countries plan their futures, invest their resources and track their progress.

-

Does NAP stand for “National Adaptation Plan” or “National Adaptation Planning”?

Within the context of UNFCCC discussions, NAP stands for “National Adaptation Plan” and the formulating and implementing of NAPs is referred to as the “NAP process.” This reflects that there is both a document (plan) and process (planning) associated with the endeavour. The term “national adaptation planning” is also often used to describe the process itself (instead of “NAP process”).

In regular conversation and practice with relevant stakeholders, it does not matter which term is used; what is important is that everybody has a shared understanding that it is a process for identifying and addressing a country’s priorities for adapting to climate change.

HISTORY OF NAPS AND THE NAP PROCESS

-

When (and why) was the NAP process established?

The NAP process was formally established in 2010 under the Cancun Adaptation Framework, which was an outcome of the 16th Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC. It was established to help countries embed adaptation in core development decision making to ensure that it is not treated as a separate environmental issue.

The NAP process was also put in place to make sure countries look at adaptation over the medium and longer terms—a shift from ad hoc, project-based adaptation interventions focused on short-term needs toward more strategic and programmatic approaches to adaptation.

Many countries were making efforts to identify adaptation needs and integrate them into their decision-making processes before 2010 (see below). The NAP process builds on this work and seeks to scale up adaptation.

-

Didn’t national adaptation planning happen before the NAP process was formally established?

Absolutely. The NAP process isn’t the first attempt under the UNFCCC to facilitate adaptation planning in developing countries. In 2001, Least Developed Countries (LDCs) were invited to develop National Adaptation Programmes of Action (NAPAs), which aimed to identify urgent and immediate adaptation needs. Over 50 LDCs responded to this call, submitting a list of prioritized adaptation projects in various sectors (UNFCCC, 2017).

The key difference between NAPAs and NAPs is that while NAPAs focused on short-term adaptation needs and priorities, the NAP process seeks to identify and address medium- and long-term adaptation needs. That said, NAP processes in LDCs should build on the experience of their NAPAs.

Apart from NAPAs, and outside of the formal UNFCCC process, many countries were already developing adaptation plans and/or integrating adaptation into development decision making prior to 2010. This included developing overarching national adaptation strategies, sector-based plans and plans at sub-national levels. The NAP process is an opportunity to pull these efforts together into a cohesive whole and build on them in a coordinated approach.

-

How has the NAP process evolved since it was established?

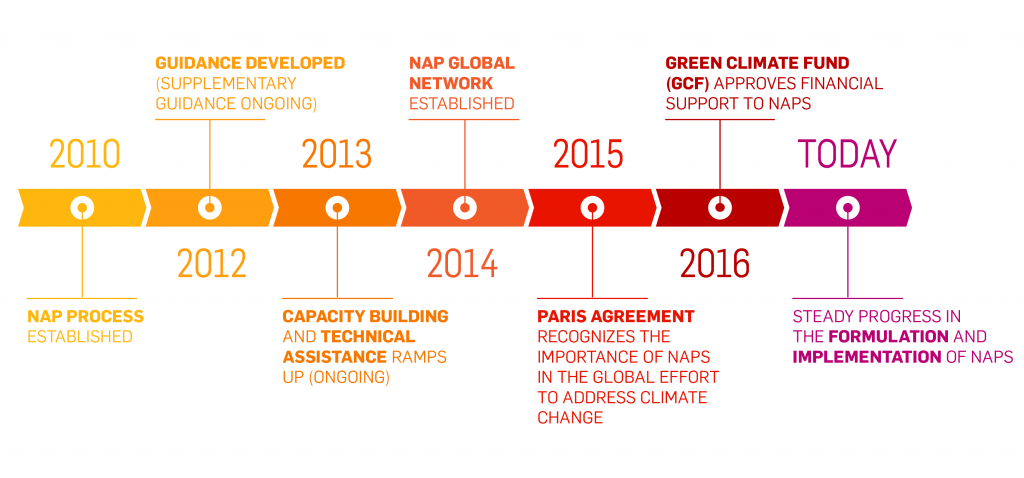

2010: NAP PROCESS ESTABLISHED

The NAP process is formally established at the 16th Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC under the Cancun Adaptation Framework, which has the objective of strengthening action on adaptation in developing countries.

2012: GUIDANCE DEVELOPED (SUPPLEMENTARY GUIDANCE ONGOING)

A set of technical guidelines is released by the Least Developed Country (LDC) Expert Group

(LEG), the UNFCCC body tasked with providing support to LDCs in the NAP process.Building on the UNFCCC technical guidelines, a number of actors have developed supplementary guidance for the NAP process on key issues, such as vertical integration, finance and climate services.

2013: CAPACITY BUILDING AND TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE RAMPS UP (ONGOING)

The first NAP Expo is held in June to launch the NAP process in LDCs. NAP Expos are held almost every year now, bringing together country teams, organizations, agencies and other stakeholders to share experiences, mobilize action and support, and identify gaps and needs around the NAP process.

That same month, the joint UNDP and UN Environment NAP Global Support Programme (NAP-GSP) is launched to assist LDCs—and later, developing countries more broadly—in identifying their technical, institutional and financial needs to integrate climate change adaptation into national planning and financing.

Capacity building and technical assistance on NAPs continues to this day with more donors, organizations and working to advance NAP processes in developing countries.

2014: NAP GLOBAL NETWORK ESTABLISHED

The NAP Global Network is established at the 14th Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC in Lima, Peru, by a group of representatives from seven developing countries (Brazil, Jamaica, Malawi, Peru, Philippines, South Africa, and Togo,) and four bilateral agencies (Germany, Japan, UK, and US). The aim is to offer a global platform for peer learning and exchange, tailored technical assistance to developing countries, and enhanced bilateral donor coordination around NAPs. The Network will complement efforts already underway by other NAP support programs, such as the NAP-GSP.

2015: PARIS AGREEMENT RECOGNIZES THE IMPORTANCE OF NAPS IN THE GLOBAL EFFORT TO ADDRESS CLIMATE CHANGE

At the 21st Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC in Paris, France, 195 countries adopt the Paris Agreement, a global agreement to tackle climate change and its negative impacts. Article 7 paragraph 9 of the Agreement states that “each party shall, as appropriate, engage in adaptation planning processes and the implementation of actions, including the development or enhancement of relevant plans, policies and/or contributions.” This is the only paragraph under the article on adaptation that obliges countries to take action, making the NAP process central to meeting the goals of the Paris Agreement.

At the same meeting, the Conference of the Parties requests the Green Climate Fund (GCF) to expedite support for the formulation of NAPs and subsequent implementation of policies, projects and programs therein.

2016: GREEN CLIMATE FUND (GCF) APPROVES FINANCIAL SUPPORT TO NAPS

In response to the request made in Paris, which recognized that support to the NAP process was often ad hoc, project-driven, and overall insufficient, the GCF Board approves financial support for the formulation of NAPs. Developing countries can access up to USD 3 million each for “national adaptation planning and other adaptation planning processes” through its Readiness and Preparatory Support Programme (GCF Board decision B.13/09, paragraph (e)).

TODAY: STEADY PROGRESS IN THE FORMULATION AND IMPLEMENTATION OF NAPS.

Overall progress in NAPs has been steady, although slower than desired—particularly among LDCs. The UNFCCC reported in December 2019 that 120 developing countries have at least initiated NAP processes and are advancing them in different ways. Whether it is undertaking vulnerability assessments, establishing the institutional structures for adaptation decision making, identifying and prioritizing options, or securing resources to implement these options—countries are moving forward. As of November 2019, 32 countries had secured GCF funding for NAPs, and 16 countries have submitted their NAP documents to NAP Central (although this does not reflect the full number of documents that have actually been produced, as some have not yet been communicated to the UNFCCC).

THE NAP PROCESS ITSELF

-

What does the NAP process actually involve?

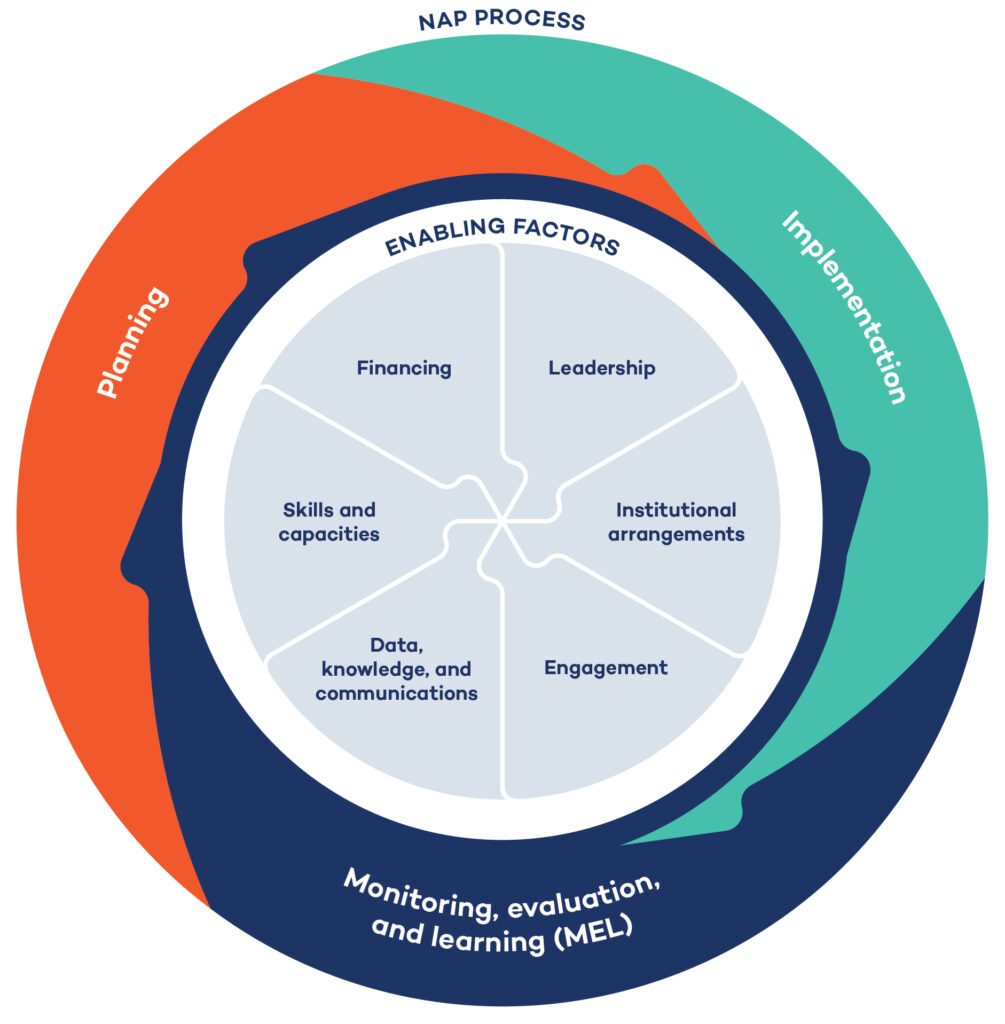

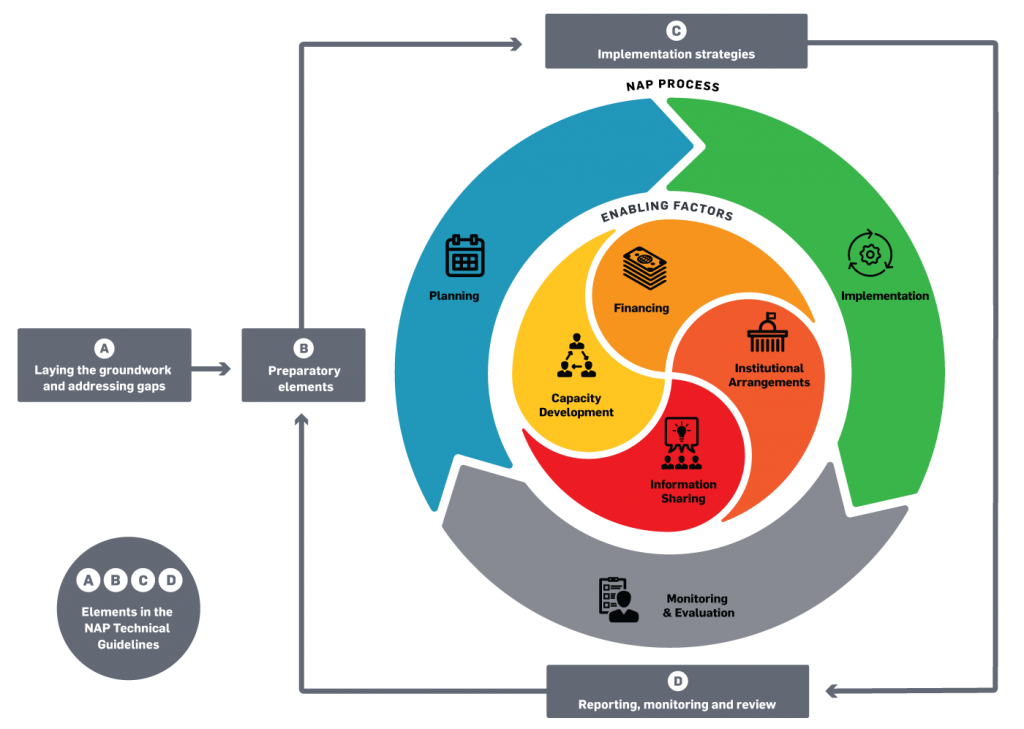

The NAP process can be thought of as three broad phases—planning, implementation and M&E—all of which are supported by capacity development, financing, appropriate institutional arrangements, and information sharing among the different actors involved. During the planning phase, climate-related vulnerabilities and risks are assessed, options for managing these risks are identified and prioritized, and strategies for their implementation developed. During the implementation phase, these strategies are fleshed out in greater detail, financing secured, and necessary technical and human resources procured and deployed. Progress, results and lessons from implementing the strategies are tracked and reported as part of M&E.

The technical guidelines for the NAP process developed by the Least Developed Countries Expert Group (LEG) note four elements to the NAP process: A. Lay the groundwork and address gaps; B. Preparatory elements; C. Implementation strategies; D. Reporting, monitoring, and review. These correspond to the three phases described above and shown below, with phases A and B corresponding to “planning,” phase C to both “planning” and “implementation” and phase D to “M&E.”

-

Wait, the NAP process is about more than planning?

Yes. It is a bit confusing since the word “plan” of course appears in “NAP,” but—as depicted in the figure above—the NAP process does involve more than just planning. Indeed, using the term, “NAP process” is an attempt to emphasize that adaptation planning leads to something more—namely, implementation of action on the ground.

While robust planning—from assessing vulnerabilities and risks, to prioritizing adaptation needs, to identifying capacity gaps—is the foundation for meaningful adaptation action, it cannot stop there. All the resources that are invested into developing good plans, strategies, and policies must be translated into tangible efforts that reduce the vulnerability of people and places to the impacts of climate change; this is also why producing a NAP document cannot be seen as the most important result of a NAP process.

-

Is the NAP a document or a process?

Both. But one of the most important things to emphasize is that national adaptation planning is a process—it is a continuous cycle of planning, implementation and monitoring and evaluation (M&E), adjusted over time based on feedback and lessons. That is, as countries discover what works and what does not work in their particular context, the NAP process should be improved.

Publishing a NAP document that presents the country’s approach and priorities for adaptation can be an important milestone in many countries’ NAP processes. But some countries may choose not to develop a new NAP document if, for example, they already have a policy document that sets out their climate change adaptation priorities. Still others are developing multiple documents over the course of their NAP process, which may include sector adaptation plans and/or strategies.

Whatever a country’s approach to producing a NAP document, it is important to note that it is just one step of the broader process. In other words, the NAP process does not end with a document. Countries that have completed NAP documents continue to invest in their NAP processes by regularly assessing climate risks, engaging stakeholders, building capacities, identifying sources of finance for implementation, tracking and reporting on their progress, and revisiting stated adaptation priorities.

-

But the NAP process is focused at the *national* level…right?

Yes, but sub-national actors have an important role to play!

Again, the word “national” in “NAP” would lead you to believe that the process is targeted solely at stakeholders and institutions operating at the national level—e.g., central or federal governments, sector ministries, departments, etc. This is not strictly the case, however.

Successful NAP processes create intentional and strategic linkages between national and sub-national adaptation planning, implementation, and M&E—we often use the term “vertical integration.”

Establishing and maintaining these national–sub-national linkages ensures that local realities are reflected in the NAP process and that the national-level process enables adaptation at sub-national levels, including at local or community levels. And while priorities may be identified through a nationally driven process, implementing actions to address them will inevitably involve sub-national actors such as local authorities and civil society organizations. Without these actors, it will be difficult to achieve adaptation outcomes on a broad scale.

-

How can a process that often involves creating separate adaptation plans also be about integrating adaptation into existing development planning and decision making?

Because priority setting and planning are important steps towards integration. The climate vulnerability and risk assessment process allows countries to identify and prioritize adaptation actions, which can then be integrated into its development plans and processes. Often, this involves the development of a separate adaptation plan; however this does not mean that a country has forgone integration. On the contrary, this provides a basis for stakeholders to understand what needs to be done, why and how—elaborating the what for integrating adaptation in plans, policies and budgets.

At the same time, countries are working to sort out the how—adjusting government procedures and processes to integrate climate change into decision making so that adaptation becomes part of everyday business.

These two processes may seem at odds with each other, but they can be mutually reinforcing and happen concurrently. This allows countries to move forward on identifying and addressing adaptation priorities, while also adjusting systems and decision-making processes to make adaptation a core part of a country’s approach to development. The iterative nature of the NAP process allows for this, providing countries with the flexibility to take a phased approach to integrating adaptation over time.

GUIDANCE ON NAPS

-

Are there guidelines for the NAP process?

Yes. In 2012, the Least Developed Country (LDC) Expert Group (LEG), the UNFCCC body tasked with providing support to LDCs in the NAP process, developed technical guidelines that outline the key steps involved in the process. While recognizing that the NAP process must be country-driven and context-specific, these guidelines provide a roadmap for countries in advancing their NAP processes (UNFCCC, 2012). A range of supplementary materials, which offer more focused or in-depth guidance on different aspects of the LEG Technical Guidelines, is also available.

-

Do these LEG Technical Guidelines correspond to the NAP process diagram presented above?

Yes. Both the LEG Technical Guidelines and the NAP process diagram convey the same process—in fact, you can easily map them against each other. The Technical Guidelines note four elements: A. Lay the Groundwork and Address Gaps; B. Preparatory Elements; C. Implementation Strategies; D. Reporting, Monitoring, and Review. Under each element are a series of 4-5 steps. Broadly speaking, phases A and B can fall under “planning,” phase C under both “planning” and “implementation” and phase D under “M&E” of the NAP process cycle.

-

What is an effective NAP process?

Building on what has been decided through the UNFCCC decisions around enhanced action on adaptation, the NAP process should be:

- Country-driven: Where countries decide what approach, process and deliverables are best suited to identifying and addressing their adaptation priorities.

- Gender-responsive: Where gender differences in adaptation needs and capacities are recognized, participation and influence in decisions equitable, and benefits resulting from investments in adaptation equitably accessible.

- Participatory and fully transparent: Where a wide range of stakeholders both within and outside of government—i.e., sub-national authorities, academia, civil society, the private sector—can take part in the NAP process, and the process itself is open, communicative and accountable.

- Inclusive of vulnerable groups, communities and ecosystems: Ensuring that adaptation investments are targeted where they are needed most, recognizing the acute vulnerability of marginalized groups and communities and the need to protect and build resilience of ecosystems.

- Multi-sectoral, where inputs and commitment from multiple sectors and ministries—not just that of the environment ministry—are secured and sustained. Climate-sensitive sectors (e.g., agriculture, health, water and sanitation, infrastructure), as well as the planning and finance ministries must be at the table.

- Guided by the best available science and, as appropriate, traditional and Indigenous knowledge: Informed by the latest validated data and information on climate risks and vulnerability, recognizing that there will be uncertainties and limitations. This can also include drawing from the knowledge, innovations and practices of Indigenous and local communities.

- Continuous: Established and managed with an expectation that a country’s climate risks and adaptation needs will be assessed on an ongoing basis; it is a sustained process of revisiting priorities and integrating them in decision making.

- Iterative: Related to “continuous,” the process should be adjusted and repeated to consider new data and information, as well as lessons and results from previous phases and rounds so that it improves.

- Coordinated, avoiding duplication so that the different analyses, consultations, and outputs that comprise a NAP process do not repeat what has already been done or is underway through other initiatives; indeed, the aim is to bring different adaptation efforts together so they can build on each other and offer a more consolidated and coherent articulation of a country’s adaptation priorities.

-

What about a NAP document—is there a recommended structure, table of contents or other specific criteria?

There is no one-size-fits-all template for a national adaptation plan document. The most important thing is that countries develop something that is meaningful and useful in their respective contexts.

In terms of structure, some countries may opt for one single overarching National Adaptation Plan; others may decide that separate sectoral adaptation plans/strategies make more sense. Yet others may do both—i.e., develop an overarching plan supplemented by stand-alone sectoral plans/strategies. Again, there is no single approach—a country’s NAP team needs to assess what works best in their country’s context.

For content, the most important thing is for a country to describe its medium- and long-term adaptation needs and priorities along with strategies for addressing them. This could be accompanied by a country’s longer-term vision for adaptation, as well as the principles, perceived purpose, scope and added value of its NAP process. Some institutional context might also be provided, where relationships between the NAP process and other relevant policies and plans are described.

The extent to which countries dedicate sections of their NAP document(s) to summarizing the risk and vulnerability context, adaptation efforts to date, the governance structures behind adaptation decision making, or the process underpinning the development of the NAP document itself—this is at each country’s discretion.

Whatever the structure and range of content, NAP documents should be strategic. They should not only clearly articulate a country’s adaptation priorities, but also define how they will be achieved, by whom, and over what time frame. Both in-country stakeholders and external actors—such as development partners and private sector investors—should see it as a guide for where adaptation investments are needed. Ideally, the document should also describe what the next steps in the NAP process will involve.

Whatever approach is taken, countries should remember that the process behind the development of a NAP document is just as important—if not more—than what gets published. A document is not the end goal of a NAP process.

-

Speaking of NAP documents—what is the difference between a NAP roadmap, NAP framework and NAP document?

The NAP process often involves the development of several documents—not just a final adaptation plan or set of adaptation plans. The most common amongst these are:

- NAP roadmap, which provides an overview of what needs to be done for the NAP process; it spells out the key steps, activities, roles and responsibilities, necessary resources, and timeframe for the NAP process.

- NAP framework, which provides an overarching vision and structure for the NAP process, including an articulation of its added value. It describes the mandate, objectives, principles and overall approach of the NAP process, and aligns it with the broader policy landscape. It may also go as far as identifying specific sectors and themes that are especially relevant to the country’s context.

- NAP document(s), which is a strategic document (or set of documents) that identify a country’s medium- and long-term adaptation priorities, and the strategies for addressing and tracking them. It can also describe how a country will go about embedding adaptation into its development planning, decision-making and budgeting processes.

Once a final NAP document is produced, other documents may be developed to push the plan towards implementation. These may include implementation plans, resource mobilization strategies, financing strategies, concept notes and funding proposals.

KEY ISSUES FOR NAP PROCESSES

-

What is a gender-responsive NAP process?

One of the characteristics of an effective NAP process is that it is gender-responsive. This means that the NAP process actively promotes gender equality, while recognizing that gender intersects with other socioeconomic factors to influence vulnerability to climate change and adaptive capacity.

A gender-responsive approach to the NAP process addresses gender differences in adaptation needs and capacities and ensures gender-equitable participation in adaptation decision making. This increases the likelihood that adaptation investments will yield equitable benefits for people of all genders and social groups, including those who are particularly vulnerable.

This toolkit, developed by the NAP Global Network in collaboration with the LEG and the Adaptation Committee, provides practical guidance on taking a gender-responsive approach to the NAP process.

-

Why and how can the private sector be engaged in the NAP process?

Though NAP processes are led and managed by national governments, private sector actors—including both private enterprises and private financiers—need to be among the stakeholders involved in NAP processes given the significant role they play in shaping economies and livelihoods. In developing countries, micro-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) make up 60 per cent of employment and contribute an average of 50 per cent of GDP. Without the private sector’s involvement, adaptation will not be able to take place at scale.

The private sector should be engaged throughout the NAP process—through planning, implementation, and monitoring and evaluation. But in order to engage effectively, these actors need governments to create an enabling environment for their engagement, removing barriers (whether these are institutional, financial, regulatory, informational, or capacity barriers) and providing incentives for engaging. Partnering with business multipliers—such as chambers of commerce and business associations—can be an important way for governments to reach private sector actors.

The Network has published guidance for NAP teams on engaging the private sector in national adaptation planning.

-

How is the NAP process linked to the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR)?

At a strategic level, the Sendai Framework recognizes climate change as a driver of disaster risk and that addressing climate change is also an opportunity to reduce disaster risk. By helping countries to assess climate risk and increase resilience, NAP processes can help countries to achieve the goal of the Sendai Framework and make DRR more resilient to future changes in climate.

Looking at the country level, many NAP processes explicitly consider DRR—either as a stand-alone priority or a cross-cutting theme—and can therefore help countries implement the Sendai Framework. For example, one of the seven Targets in the Sendai Framework—Target E—is to “substantially increase the number of countries with national or local disaster risk reduction strategies by 2020.”

Moreover, the different stages and enabling factors of the NAP process can reinforce country efforts to address the four Priorities for Action under Sendai, which are 1) understanding disaster risk (e.g., through vulnerability and risk assessments for the NAP); 2) strengthening DRR governance (e.g., through better institutional arrangements that link DRR and adaptation); 3) finance (by attracting more investments into adaptation priorities that overlap with DRR); and 4) enhanced disaster preparedness (by calling for more disaster preparedness and response measures in the NAP).

NAPS AND THE PARIS AGREEMENT

-

Are NAPs the adaptation equivalent of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs)?

No. NDCs are pledges countries make towards achieving the objectives of the Paris Agreement. Specifically, they include the targets, policies, and actions a country will pursue to limit global temperature increase and, as appropriate, adapt to climate change. Information on a country’s mitigation efforts is mandatory, whereas that related to adaptation is voluntary. However, about 75 per cent of all countries who submitted NDCs have chosen to include actions on adaptation.

NAPs and the NAP process, on the other hand, pre-date the Paris agreement and were established for a different purpose. The NAP process is focused on countries identifying, addressing and reviewing their adaptation priorities while working to embed adaptation in their development decision-making apparatuses. The goals and priorities identified through a country’s NAP process can certainly be included in its NDC, and the NAP process itself be a means of operationalizing adaptation commitments that appear in the NDC. Indeed, NAPs and NDCs can be mutually reinforcing (see more below).

-

Are NAPs part of the Paris Agreement?

Yes. Article 7 of the Paris Agreement is devoted to adaptation. Under paragraph 9, it states that “each party shall, as appropriate, engage in adaptation planning processes and the implementation of actions, including the development or enhancement of relevant plans, policies and/or contributions.” This is the only paragraph under Article 7 that obliges countries to take action, making the NAP process central to meeting the goals of the Paris Agreement.

-

So how *is* the NAP process linked to NDCs?

The links between the NAP and NDC processes largely depend on timing and/or sequencing. A country that already has a NAP process underway can draw from it to define the adaptation targets, policies, and actions to be included in an NDC. Equally, the NAP process offers a vehicle for implementing adaptation commitments included in an NDC. As NDCs are updated every five years, countries can potentially use the NDC cycle to regularly revisit the priorities included in the NAP, if appropriate.

A country that does not yet have a NAP process underway may choose to include a commitment to launch one as part of its NDC, along with an overarching vision and framework for adaptation. As NDCs are externally-facing pledges, the adaptation component of NDCs may help to raise the profile and garner further support for the NAP process.

Ideally, the NAP process and the adaptation component of NDCs will be aligned so that they articulate the same objectives, are informed by the same datasets and analyses, and tracked using the same metrics.

SUMMARY

-

Why is it important for countries to engage in NAP processes?

There are several reasons why countries should engage in the NAP process. Among the most important are:

First, it can improve development practice and outcomes. NAP processes aim to enhance standard government processes and decision making; they integrate climate risk and priority adaptation actions into development plans and budgets, thereby directing investments into resilient solutions. In so doing, NAP processes can ultimately help countries adjust their development pathways in order to minimize vulnerabilities and thrive in the face of climate change.

Second, the NAP process can help countries better access and use finance for adaptation. Globally, commitments to adaptation finance are increasing. Having a NAP process in place demonstrates that countries are clear about their priorities for using this funding, and that they have invested in the institutions and practices needed to channel and use this funding effectively.

Third, it helps countries to implement the Paris Agreement. Under Article 7 of the Agreement, countries agree to “engage in adaptation planning processes and the implementation of actions, including the development or enhancement of relevant plans, policies and/or contributions.” Also, most countries have opted to include adaptation commitments in their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), which outline a country’s actions for meeting the Paris Agreement goals. Countries can also use their NAP process and/or documents to develop and/or submit an adaptation communication and prepare the adaptation section of their biennial transparency report, should they choose.

Fourth, the NAP process can drive progress towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which established the SDGs, reinforced the need for action on adaptation, both as a goal in and of itself and as a means to achieving other goals in areas such as food security and water. The NAP process provides a means to operationalize these global goals.

Fifth, it can help advance progress in implementing the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR). By helping countries to understand risk and build resilience, the NAP process can help meet the goal of Sendai. Specifically, NAP processes that explicitly consider DRR—either as a stand-alone priority or a cross-cutting theme—can help countries to meet the Targets and address the Priorities for Action under the Framework.

-

Where can I find out more?

For more information on the NAP process, check out the UNFCCC’s NAP Central and our own resource library.

Further reading

Adaptation Community. (2018). Tool for assessing adaptation in the NDCs (TAAN): Quick facts. Retrieved from https://www.adaptationcommunity.net/nap-ndc/tool-assessing-adaptation-ndcs-taan/taan/

UNFCCC. (2010). The Cancun Agreements: Outcome of the work of the Ad Hoc Working Group on Long-term Cooperative Action under the Convention (Decision 1/CP.16). Retrieved from https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/docs/2010/cop16/eng/07a01.pdf?download

UNFCCC. (2012). National Adaptation Plans: Technical guidelines for the national adaptation plan process. LDC Expert Group, December 2012. Retrieved from https://unfccc.int/files/adaptation/cancun_adaptation_framework/national_adaptation_plans/application/pdf/naptechguidelines_eng_low_res.pdf

UNFCCC. (2015). Paris Agreement. Retrieved from https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/english_paris_agreement.pdf

UNFCCC. (2017). National Adaptation Programmes of Action. Retrieved from https://unfccc.int/topics/resilience/workstreams/national-adaptation-programmes-of-action/introduction